The Art of Conducting

The conductor is by definition a person who stands center stage in front of performing musicians whose “conducting of musical measures is realized by a flow of organized body movements, usually hand movements that draw specific patterns in a 3D space around the conductor. These movement patterns are periodic and may be grouped into different sets of beats” (Schramm, Jung, & Miranda, 2015)

The conductor’s job is to realize and interpret the music, and to do so he expects “all those before him to be subject and subordinated to him” (Fredman, 2006). Without making any sound, the conductor uses his body language, arm, hand, and finger gestures, facial expressions, anger, smile, eye contact, everything that can be included under musical gestures. The conductor interprets a composition through a written musical score, which includes all necessary information about the performance, pitch, timbre, tempo, rhythm, and volume of any of the performing instruments (Johannsen et al., 2010, p. 268). The ideal conductor must learn the music beforehand, incorporate it into her neurological system, and then she must be able to express this emotion to her performers, first through her words at rehearsals and then through musical gestures at the concert. One can therefore say that “in terms of conducting, as a trained motor skill used for nonverbal communication, effective gestural cues are vital” (Visentin, Staples, Wasiak, & Shan, 2010).

Conducting

From a historical perspective, the role of the conductor has grown through the centuries. The conductor has gone from being one of the performing members of the orchestra conducting from his chair, usually the violin or the harpsichord player, to a figure standing on a podium in front of an orchestra. This change in role goes hand-in-hand with the development in size and instrumental combination of the orchestra from the Renaissance orchestra (about 400 years ago) through the Baroque and Classical orchestras to the Romantic era, which provided us with the size of orchestra we know today.

With the growth of the orchestra, the instrumentation was increasingly organized into sections and composers started to write for the specific instruments they had in mind. The term “orchestration” became important, meaning to arrange or score music for orchestra by writing a musical score. Composers also began to be more adventurous about combining instruments to produce different sounds and colors (Philharmonic., 1999, n.d.). Increased interest in new sonority led to better design and construction of the “old, traditional” instruments and new instruments, such as the clarinet, saxophone, piccolo flute, and tuba, were introduced.

Musical auxiliary signs, such as tempo signs, also came into play, usually provided in Italian, such as Adagio, Moderato, Presto (slow, moderate, fast) and later more precise metronome indications were utilized, such as quarter note = 60 (quarter note per second). Dynamic signs became prevalent, such as f(forte) loud, p (piano) soft, crescendo (cresc…) gradually louder, diminuendo (dim…) gradually softer, accelerando (accel…) faster tempo, and ritardando (rit…) gradually slower.

All these developments led to an increased interest in composing music that would enrich the sonic and rhythmical possibilities of the orchestra. It also led to an increased complexity of the orchestral score and expanded the responsibility placed on the conductor and his role as the “leader” of the orchestra. The conductor became the ultimate interpreter of the orchestra; he moved from being one of the performing members to an independent, conducting musician standing on a podium in front of the orchestra.

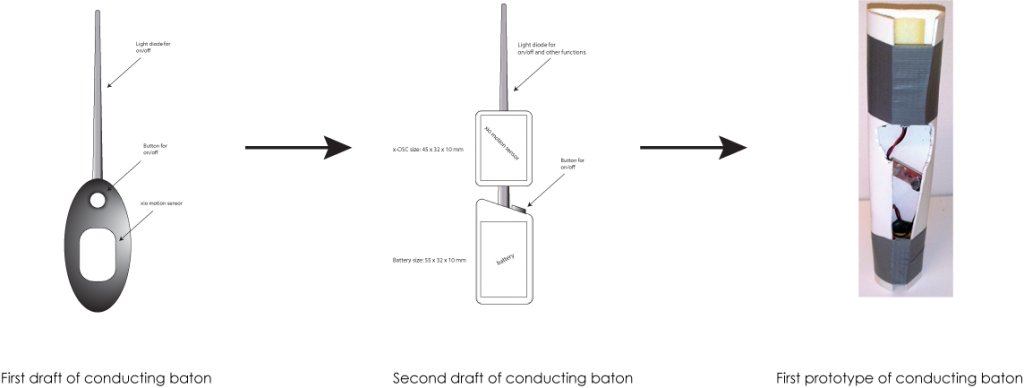

Conducting Tools

In the eighteenth century, the conductor baton was introduced as a tool to help make gestures clearer and easier for the orchestra to follow. By extending the arm of the conductor, the baton made it easier for the performers to watch for and see the conductor’s gestures. With the establishment of conducting schools in the mid-nineteenth century, gestural patterns or “rules” evolved for all metric indication, such as , , , and . Other musical gestures were also accepted and understood more generally and used for musical expression, including small gestures to indicate less volume (pianissimo) or larger gestures for more volume (forte), stiff conducting gestures for strict rhythmic playing (staccato gesture), and more curved or soft gestures for more melodic playing (legato).

The rise in complexity of twentieth-century compositions not only provoked an explosion in the harmonic language of music but also in the orchestra form. Contemporary experimental composers preferred smaller instrumental ensembles and different instrumental combinations, where the tiniest details in the written score could be illustrated through the conductor’s gestures. As a consequence, a growing number of twentieth-century contemporary music conductors preferred to use their hands rather than the baton. This way they had more control in their “fingertips” to implement the smallest details of the music.

With this historic perspective in mind, I have focused on developing a new conducting tool that is in and of itself a consequence of the historical evolution of the art of conducting. This is why the ConDiS system is a glove-based instrument.

No new tools have been developed and applied to the work of conducting over the past 100 years. It is in fact fascinating that the only development made in this time was putting aside the use of the only existing tool, the baton. The most likely explanation for this turn of affairs is that there never has been a need for tools other than the conductor’s body. The conductor’s body gestures and facial expressions are able to convey any and all exformation necessary to conduct music.

It is not until the advent of interactive mixed music performance that a new need has arisen for the development of new conducting tools. As will be explained in more detail in the next chapter, technological advances over the past several decades (since around 1980) have opened up new possibilities for developing and designing new musical instruments and conducting tools.

The Extended Conductor

The Best Musical Solution

The idea behind having the conductor conduct the electronics is that I believe it is the best “musical” solution in these cases. As I will demonstrate below, the conductor is the best-qualified person for this task. The conductor is the only person who knows the whole score by heart and is trained to synchronize and control the whole performance. It is the conductor who prepares herself by analyzing the score, and it is through the score that the conductor interprets the composer’s intentions and communicates these to the orchestra and the audience. Using the conductor instead of a sound engineer to adjust the mix between the orchestra and the electronics is simply more “natural” since this continues to correspond to the traditional job of the conductor.

One might argue that the sound engineer is better situated than the conductor for hearing the overall mix. I nevertheless believe that regardless of the conductor’s location being based on her physical connection with the orchestra rather than a connection to the overall sonic mix, it is better to have the acoustics and electronics mixed from the same point of hearing. I consider it unfortunate to have two people in charge of the overall sonic mix, one on stage front and center mixing the balance of the acoustic instrumental sounds and the other in the middle (or at the back) of the hall mixing the balance of the electronics. In this situation, if the conductor decides that the electronic sound is too loud or too soft, her only option is to adjust the sound level of the orchestra accordingly.

I must confess one oversight that only became apparent later on in this project, namely that most conductors of acoustic music find the electronic sounds to be exotic and, in some ways, disturbing. Halldis Rønning, like the majority of classical conductors, has little experience of mixing instrumental sound and electronic sound. Her experience is therefore considerably different from my own. I have worked with electronic sounds for decades, and they are a part of my sound world. Halldis, on the other hand, has worked mostly in the world of acoustic instrumental sound. These electronic sounds are consequently not part of her sound world. It was therefore fascinating, if challenging at the same time, to witness the developments that took place over the course of the performances of Kuuki no Sukima, from the first concert at Dokkhuset to the last concert at Rockheim. With these developments she became increasingly better at mixing the acoustic instruments and the electronics. This had the additional effect of making the performances more relaxed with a more precise formation of the music.

It was noticeable that Halldis lowered the overall electronic sound levels during concerts where, due to the better location of the speakers, she heard the electronics more clearly. This might be explained straightforwardly with the observation that better hearing caused her to lower the volume. But I nevertheless felt that hearing the electronics more distinctly ended up disturbing her from hearing her familiar “classical” instrumental sound. And this led her unconsciously to lower the electronic volumes.

This discovery was unexpected, but not surprising. It is my opinion that ConDiS is a very exotic tool for the conductor. It is not only an extension of the job of conducting, it is an extension of the conductor’s sonic world. With the electronics so closely related and responding to the conductor’s gestures, the conductor becomes more aware of the electronic sounds. The conductor starts to hear the electronic sounds in a different way than before when they were just an accompaniment to the instrumental performance. The conductor starts to hear the mix of the instrumental sounds and the electronic sounds in a novel way. What is more, the performers share a similar experience. As a result the conductor, the performers, and the electronics become one: they become unified.

It is evident to me now that it will take a long time before ConDiS is regularly integrated into the performance of mixed music. This is not only because it is a new, exotic tool for the conductors, as I already acknowledged at the beginning of my research project, but also because it extends their sonic world. They need time, they need practice, they need more opportunities to use it in performance. That can only come about with the production of new compositions incorporating the results of the ConDiS project.