To utter my reflections, analyze of the written musical score are made in conjunction with audio and video recordings made during the performances. There I reflect on the composition and the conductor’s use of ConDiS as well as the performance. Emphasizing both the positive and negative sides.

I go through the entire artistic evaluation process of the project, focusing on its artistic gain and value. Therefore, deliberately avoiding the writing on the technical development of the project.

In an effort to simplify and thus facilitate understanding and reading, I use, as well as written text, video examples, video clips from an interview with conductor Halldis Rønning and questionnaires sent to members of the Trondheim Sinfonietta.

Process towards confidence

Given the possibility to have more than one performance of a new contemporary experimental piece is a privilege. Having more than two is beyond that and having five or more is a miracle. All the performances were recorded in different concert halls under different conditions.

Listening to the performances from the first performance at Dokkhuset (November 2017) to the last in Schæffergården (February 2018) there is a constant process towards stronger confidence resulting in greater interaction. Not only between the performers, electronics, and the conductor, but also between the conductor, ensemble and the electronics.

Kuuki no Sukima– Sonic Analyses

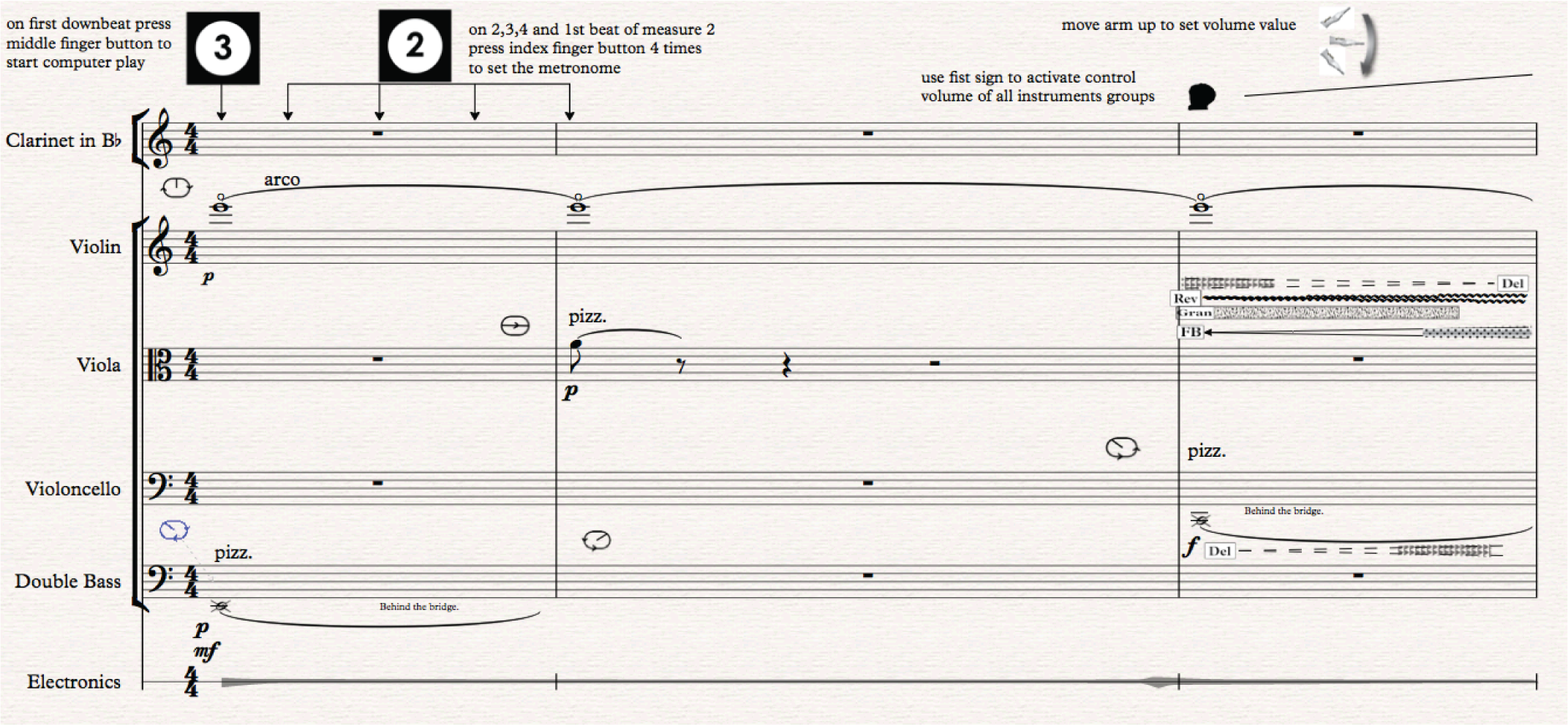

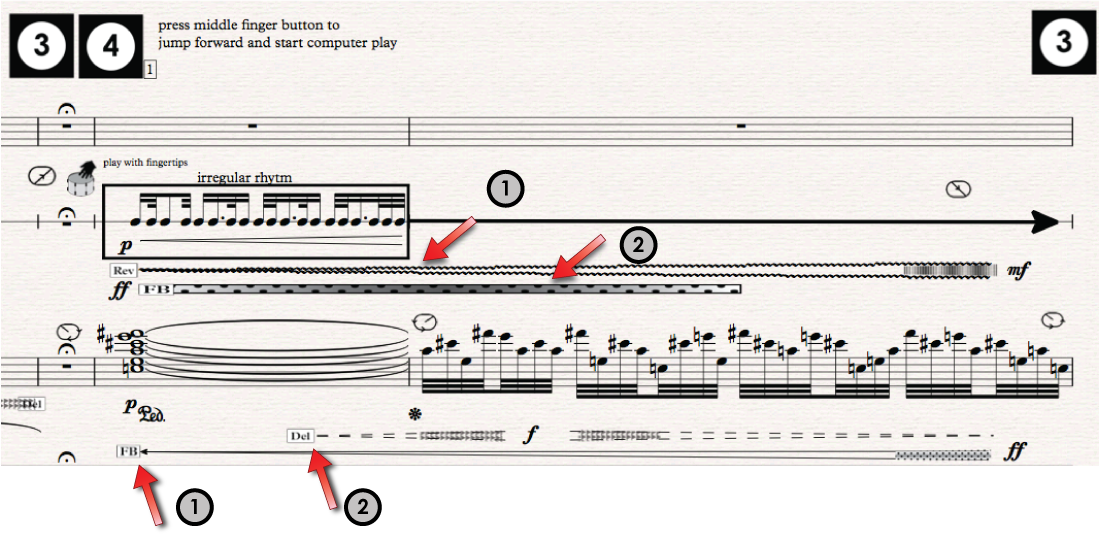

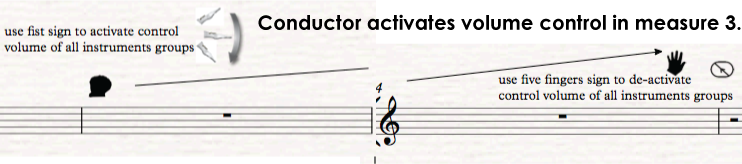

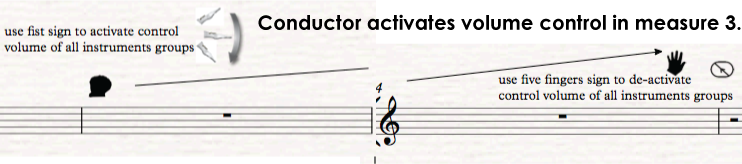

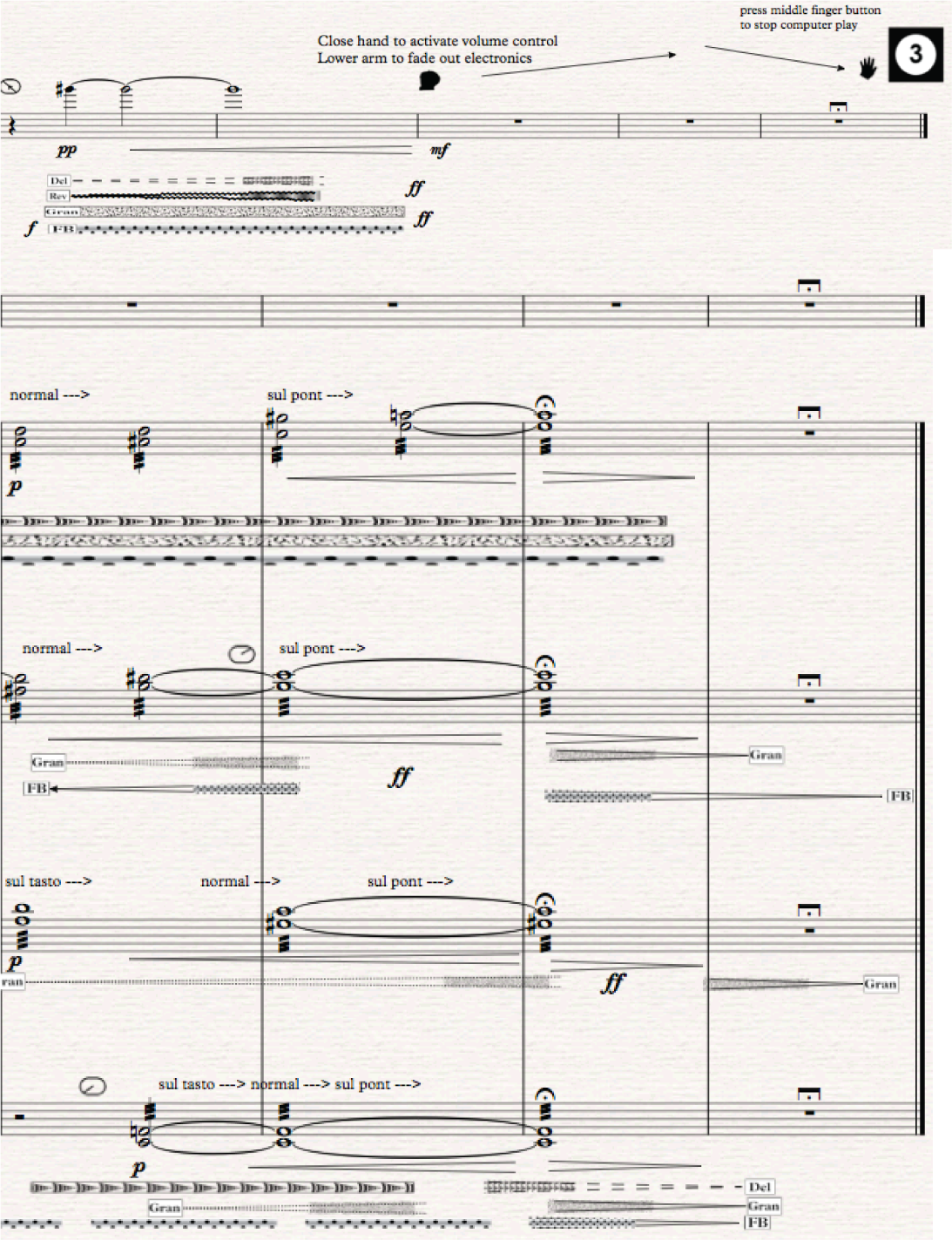

In my blog “Closer look at the Score” dated March 1st, 2018 analyzes of the conducting instructions in the opening measures of Kuuki no Sukimawere made. How the conductor had to press the start knob (3rdknob) and then the tempo knob (4thknob) four times to set the tempo and finally close her fist to activate the volume control.

Focusing on the sonic part of the concert, i.e., how the sound of the instruments interacts with the electronic sound effects of the computer. I will, showcase the relationship between written notation and sonic experience. How I use traditional notation in conjunction with “traditional” graphical interface of music software applications. Commonly called “Automation” a control whose value changes in the course of a timeline that is automated.

Sonic Analyzes

A closer look at the opening measures of Kuuki no Sukima.

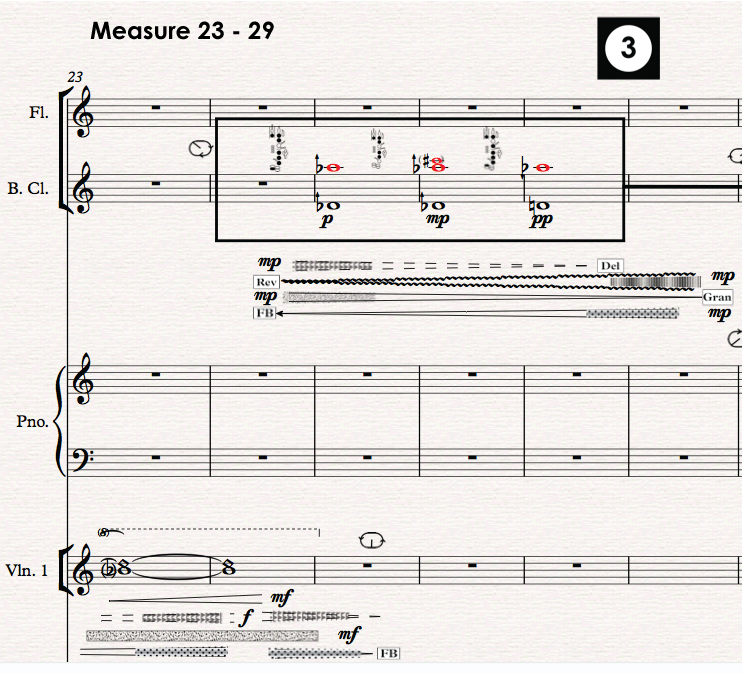

Figure 27. The opening measures of Kuuki no Sukima.

Figure 27. The opening measures of Kuuki no Sukima.

Audio example #1: The opening measures of Kuuki no Sukima

http://caveproduct.com/audio/Harp_1st.m.1-5.2.wav

In the opening measures there is no use of electronics, and therefore there is a clear dry sound of the instruments until the conductor activates the volume control by closing her fist and raise her arm. At that point, at the beginning of measure three, the conductor increases the volume of the electronic sounds from cero or no electronic sounds to the desired level. This beginning is a slight change from the original idea where the electronics were supposed to be active from the beginning. Why these changes? As mentioned earlier, this was done to simplify the actions the conductor had to perform at the beginning of the work. This way the conductor did not have to raise her arm before starting the performance to a volume of no responding sound. It is undoubtedly possible to have the volume adjusted beforehand in the DAW, but somehow that solution was not to my artistic satisfaction. Aesthetically the solution to have her raising her arm later worked out to be a stronger beginning. It gave the composition more dramatic opening with the electronics fading in with the visual and sonic realization of the conductor raising her arm.

Notated Score and the DAW Interface Connection

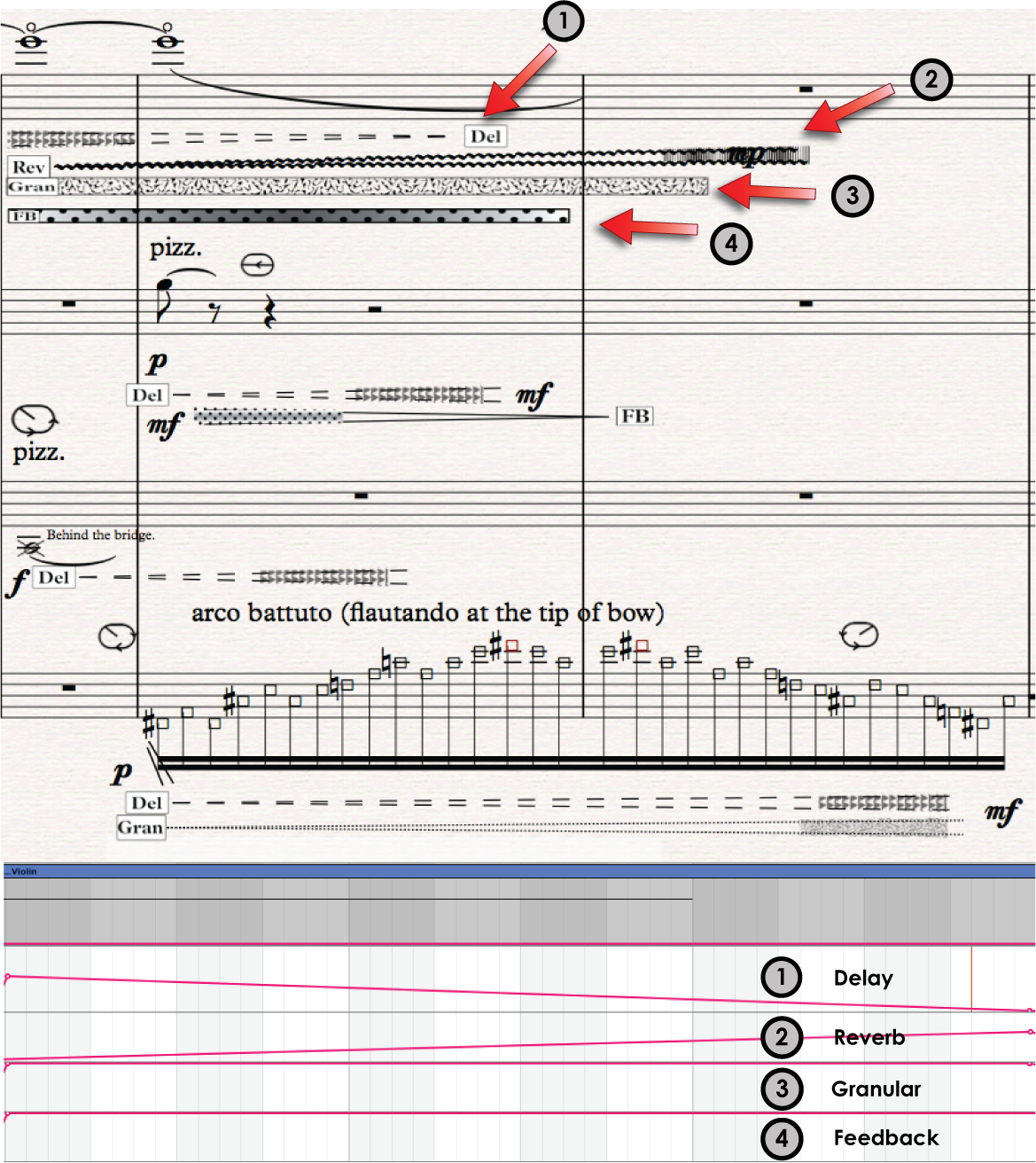

The sound of the Violin starts to change in the third measure as soon as the conductor raises her hand. The sounds of the other instruments, the pizzicato with a delay in Cello and Viola. The fast and airy note pattern (arco battuto) in the Double Bass, where delay and granulation are increasingly affecting the sound is not as clear. Why?

Let’s first take a closer look at the score and the electronic score to figure out how things are connected or related.

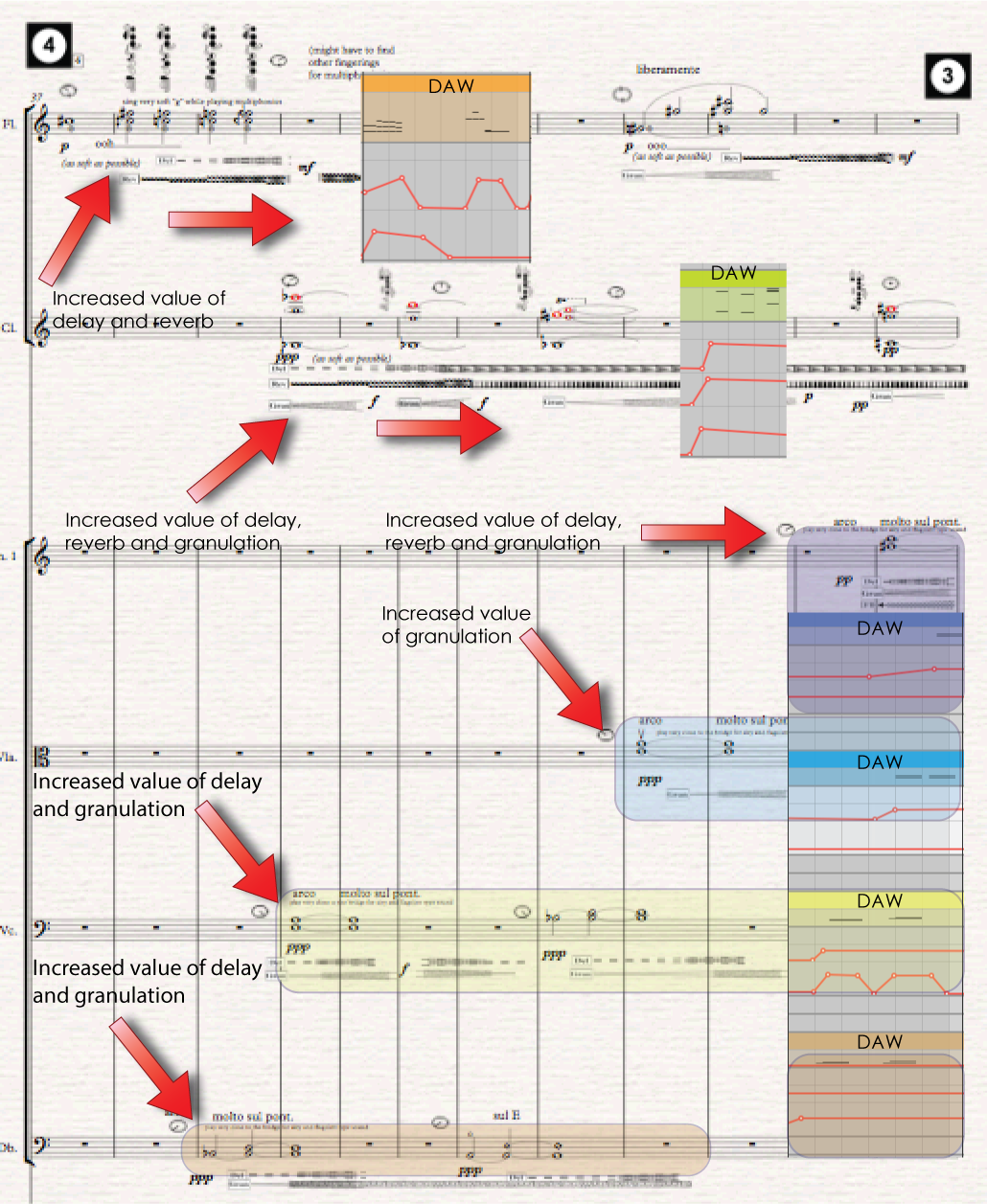

Figure 28. Kuuki no Sukima measure 3 – 6. The connection between the notated score and the graphical interface of the DAW.

Figure 28. Kuuki no Sukima measure 3 – 6. The connection between the notated score and the graphical interface of the DAW.

The above illustration shows the connection between the notated score and the graphical interface of the computer application or DAW. With a focus on the Violin part, let’s take a closer look at what electronic effects ads to the high opening note (E).

- Delay with diminuendo (decreasing volume) from approximately mf to silence.

- Reverb fades in with increasing volume to approximately mp(relatively little reverb)

- Granulationstarts with f for very strong and stays unchanged.

- Feedback starts with ff(very strong) and stays unchanged.

Audio example #2: Measure 3 – 10

http://caveproduct.com/audio/Measure-3-10.wav

Figure 29. Kuuki no Sukima measure 3 – 10.

Figure 29. Kuuki no Sukima measure 3 – 10.

The above figure shows how the other instruments, Viola, Cello and Double Bass add effects that increase or decrease in the same way as shown the Violin part. However, they are not as easily audible as the high Violin pitch, why?

Fist the loud pizzicato in Cello in measure 3 comes right at the beginning of the conductor’s increase of the electronic volume. Therefore, the expected delay effect written in the score is not audible. The following Viola pizzicato in measure 4 has an increasing delay and decreasing feedback. It can hardly be heard most likely because the pizzicato is soft (p) and the conductor still hasn’t raised the volume to its maximum value. For the same reason, Double Bass fast, airy note pattern starting in measure four is not very clear.

These use of the electronics needs to be adjusted in the next revised version.

Volume based Relation

Since all the electronic sounds are related to their instrument, there to say the electronic sound source is the sound of the Clarinet played at that time. In other words, it is a live real-time sound processing of the Clarinet. Therefore, if the Clarinet plays a soft note, the electronics are going to be soft and vice versa.

This relationship is problematic since although there is written an ff, meaning a compelling use of the effect, it does not mean that the outcoming sound is going to be loud. It means that the electronic sound is having a significant effect on the played tone whether that tone is loud or soft.

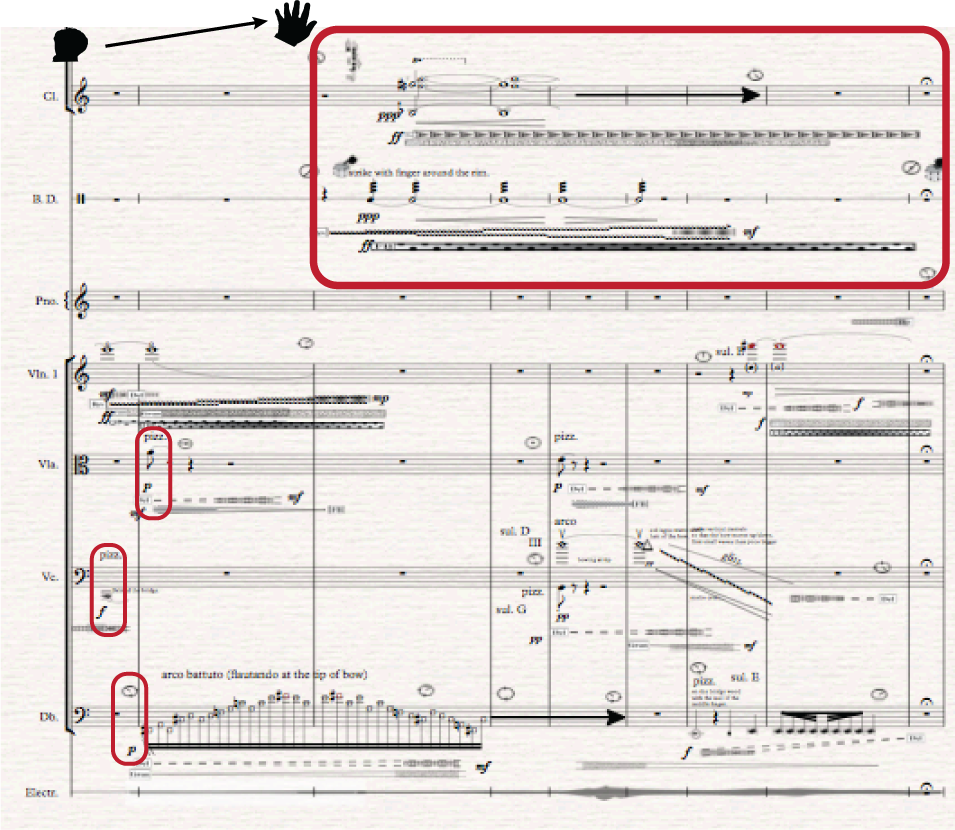

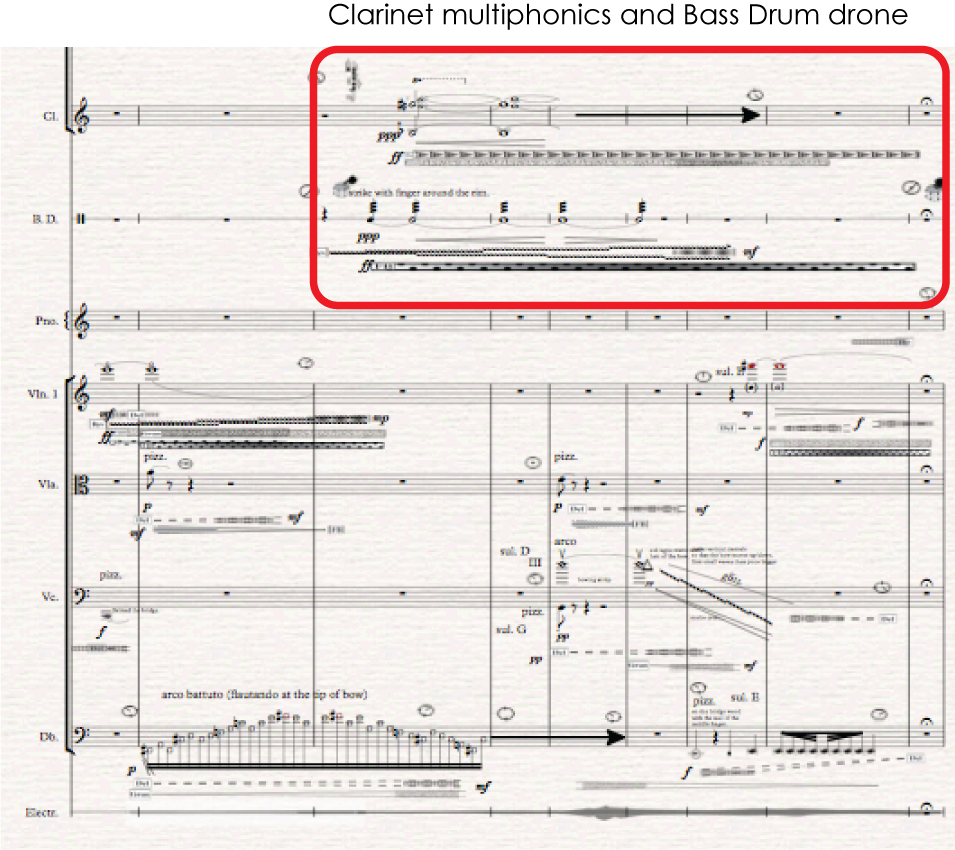

Measure five is a good example of the relationship between soft instrumental sound and “loud” electronics. The conductor has increased the electronic sound level to the desired point.I choose to use the word desired point to reassess that it does not have to be a maximum point. It is entirely up to the conductor to adjust the volume like she does when conducting the “other” instruments. Soon after the conductor has deactivated the volume level control the Bass Drum and Clarinet start to play. Figure 38 shows measures 3 – 11 where the Clarinet and Bass Drum enters at measure 5.

Listening and comparing three different performances from the concerts at Harpa in Reykjavik, Nordic House in Torshavn and Schæffergården in Copenhagen reveals that there is not a significant difference. The conductor is quite constant in her volume value settings, although I would have liked the electronic volume value to be louder. A very important fact that with use of ConDiS the control is in the “hands” of the conductor, therefore, I can disagree with her interpretation.

Figure 30. Measure 3-11 with Clarinet and Bass Drum entering in measure 5.

Figure 30. Measure 3-11 with Clarinet and Bass Drum entering in measure 5.

Audio example #3: Example measure 5-11 from Harpa Concert.

http://caveproduct.com/audio/Clar_BD_multiph.wav

Audio example #4: Example measure 5-11 from Torshavn Concert

http://caveproduct.com/audio/T_clar_BD-m.5-11_….wav

Audio example #5: Example measure 5-11 from Copenhagen Concert

http://caveproduct.com/audio/C2_Clar_BD-m.-5-1….wav

I was expecting more sound processing, especially in the Clarinet. Why? The Clarinet is playing multiphonics that are relatively high and rich in pitch. Therefore, the electronic sounds should be clear. It is a bit different from the Bass Drum that is playing a very soft deep drone that picks up fewer electronics. Although the multiphonics for the Clarinet are written as very soft (ppp) it is not possible to play them much softer than we hear on the recording. This physical problem is a perfect example of the inaccuracy of classical note writing since the ppp means as soft as possible, but the relative loudness is more like and mf (mezzoforte) or medium loud. Still, I choose to write them ppp to indicate that it should be played as soft as possible. Other facts that might count is that the conductor’s adjustment of the volume level is too soft. The Violin that enters in measure 9 supports the theory because there the conductor has increased even more the electronic sound, and therefore it is much more audible.

The opening measures from the Harpa performance with score and illustrations.

Video example #6: Kuuki no Sukimameasure 1 – 11.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/H_KnS_1st_m_1-11.mp4

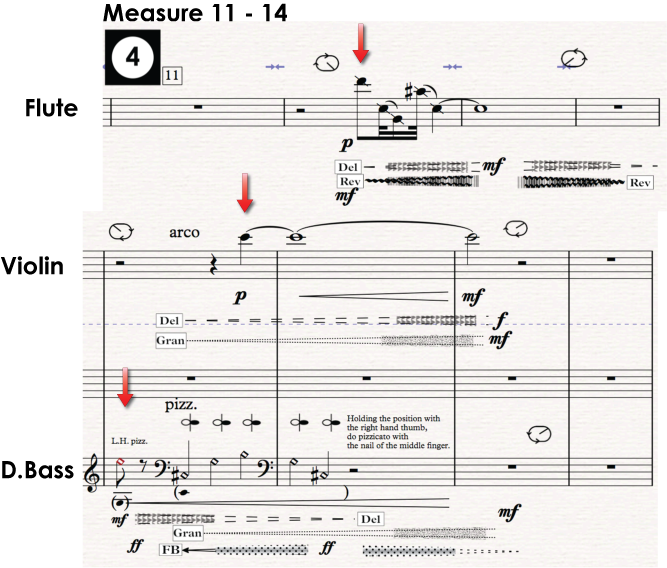

Measure 11 – 14.

In measure 11 there is a general pause where the conductor stops the play knob of the electronics by pressing the 3rdknob. After the pause, the conductor continues by pressing the 4thknob which jumps the playback-head of the DAW to precisely the beginning of measure 12. That synchronizes the DAW and the notated Score so that the Bass Drum and Piano duo should be precisely in sync with the effects of the electronics.

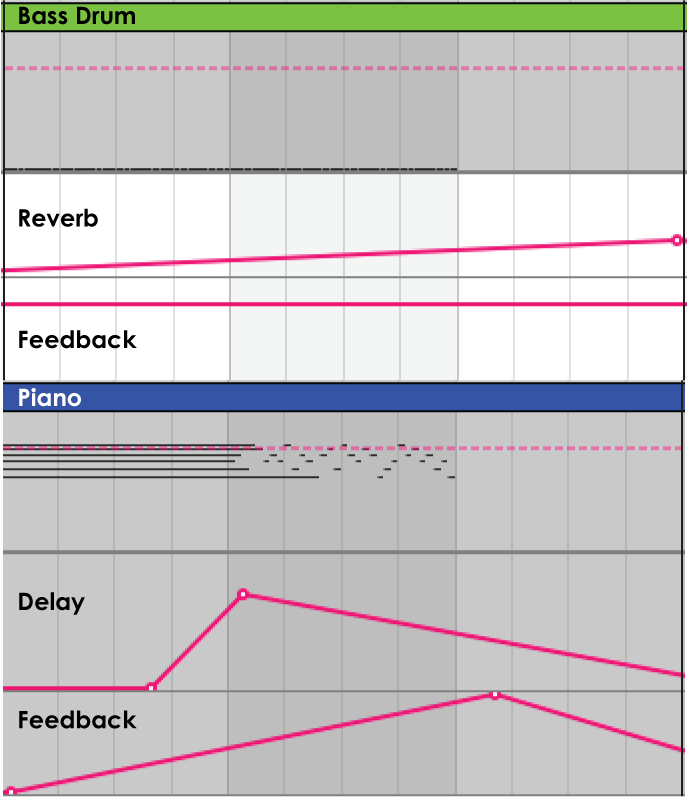

Figure 31. Kuuki no Sukima measure 11-14.

Figure 31. Kuuki no Sukima measure 11-14.

As shown in the figure above Bass Drum comes in with increased reverb and strong feedback effect while the piano has increased feedback, as well as increased —> decreased delay.

Bass Drum

- Reverb crescendo to mf(mezzoforte) medium loud.

- Feedback with unchanged ff(fortissimo) strong effect.

Piano

- Delay crescendo to f(forte) —> diminuendo to cero.

- Feedback from cero to ff (fortissimo/very strong).

Now, look at the automation for the same measures as written in the DAW.

Figure 32. The automation window of the DAW.

Figure 32. The automation window of the DAW.

The above figure shows the automation for the electronics that should be in precise synchronization with the written score. It means that when the Bass Drum starts playing its rhythm pattern, there is an increasing reverb coming in and very strong feedback. At the same time, the piano plays a chord that at the beginning should have very little electronics with increasing delay and feedback as the chord dissolves in single notes.

Audio example #6: Bass Drum and Piano duo in measure 12 – 14.

http://caveproduct.com/audio/H_Piano-m.11-15-1….wav

Measures 14 – 28

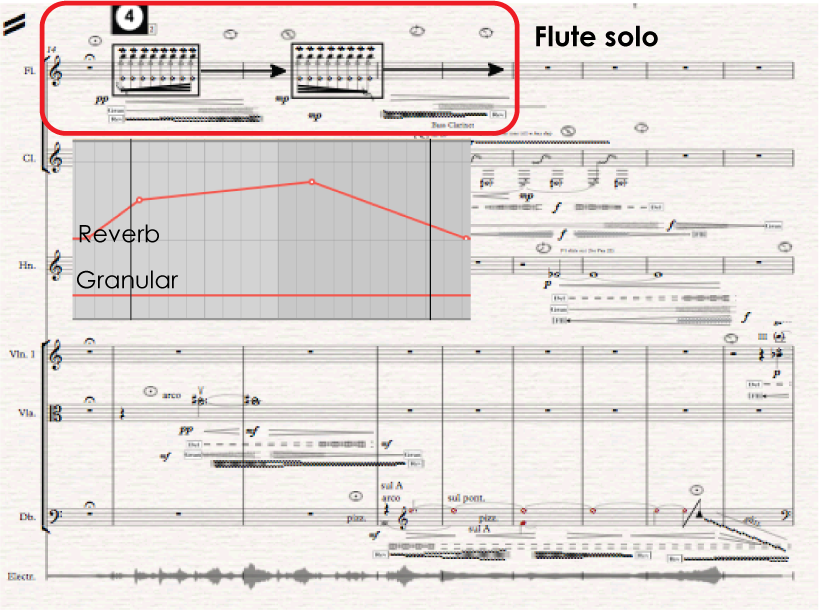

Figure 33. Kuuki no Sukima measures 14-23. Showing Reverb and Granular level written in the DAW.

Figure 33. Kuuki no Sukima measures 14-23. Showing Reverb and Granular level written in the DAW.

After the fermata pause in measure 14, the Flute starts with a solo in measure 15 that should have increased and decreased Flute, granulation and reverb sound. The following video and audio examples are various recordings of the flute solo.

First is an example made during a “read through” meeting with flutist Trine Knutsen, conductor Halldis Rønning, and composer Hilmar Thordarson without electronics. Then the same flute recording with electronics added. Finally, there are audio recordings from the Nordic Tour concerts at Harpa, Nordic House, and Schæffergården.

Video example #7: Flute solo without electronics:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Flute_1M_B12a.mp4

Video example #8: Flute solo with added electronics (computer simulation):

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Flute_1M_B12el2.mp4

Audio example #7: Flute solo from the Harpa performance.

http://caveproduct.com/audio/H_Flute-m.15-19.wav

Audio example #8: Flute solo from the Torshavn performance.

http://caveproduct.com/audio/T_Flute-m.15-19.wav

Audio example #9: Flute solo from the Copenhagen performance.

http://caveproduct.com/audio/C2_Flute-m.15-19.wav

The Flute solo begins right after a synchronization point (knob sign 4 in the score) and therefore in a 100% sync with written DAW electronics. The difference of the electronic level between the mock-up and actual concert release is evident. Why? Mock-up always gives a stronger electronic sound image than the actual version; therefore, one should expect the concert version to have reduced electronics. However, there is too much difference.

On the other hand, listening and comparing recordings from the three concerts there is very little difference. There is hardly any granular or reverb fading in and out as written. The conductor raised the volume of the electronics to an acceptable field so there should be more electronic. Most likely the automation written in the DAW needs to be adjusted especially by an increase of the granulation level.

There may also be a need to make further improvements to the position of the microphone DPA 4099HI instrument microphone (clip-on microphones).

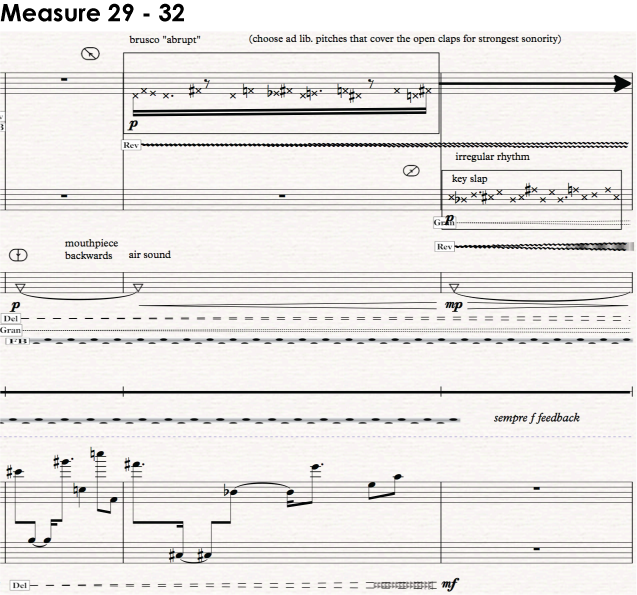

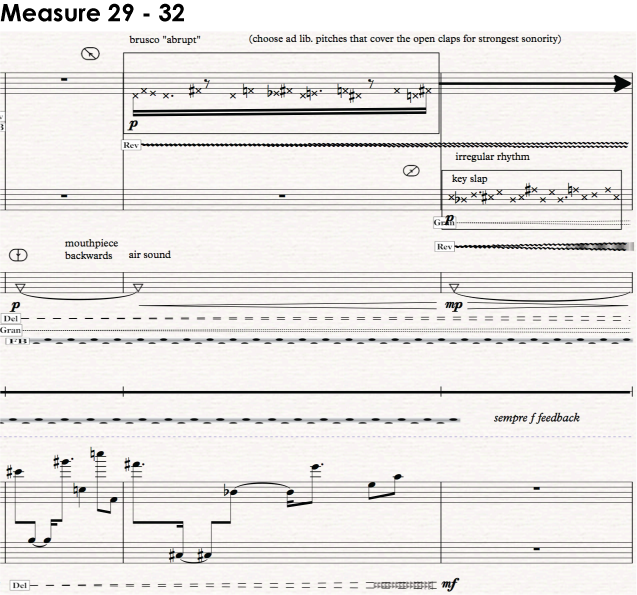

Measure 25 – 32

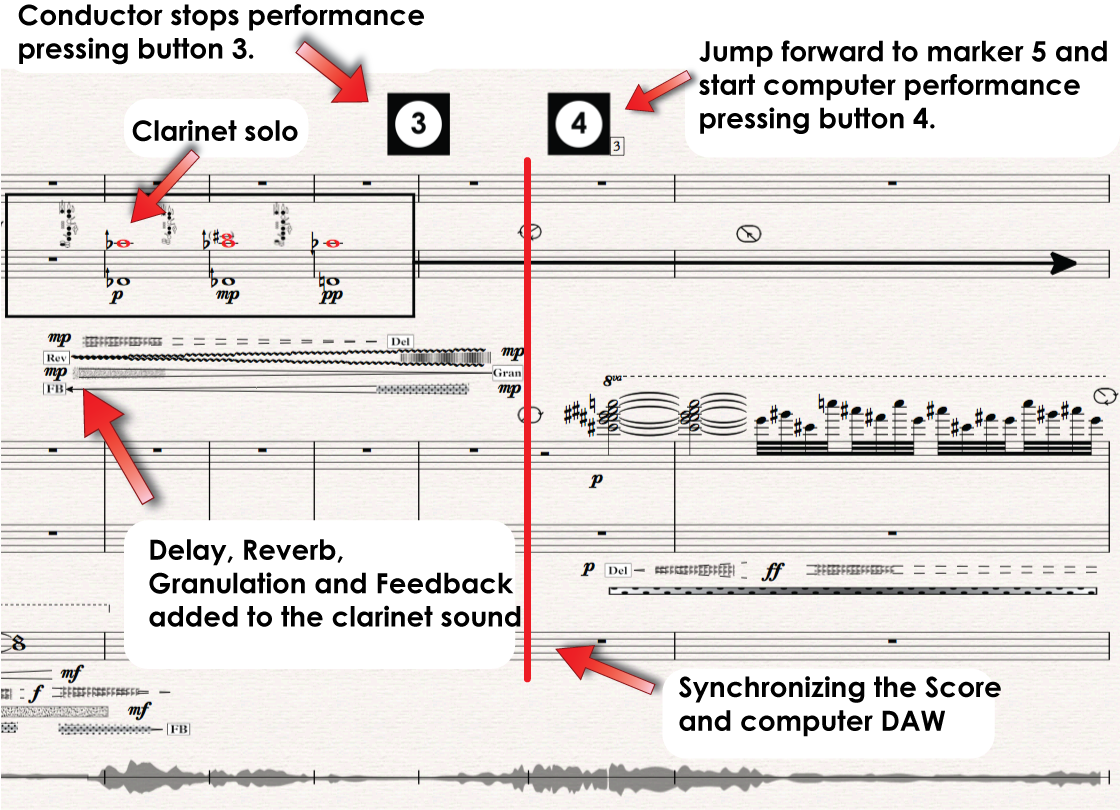

Figure 34. Kuuki no Sukima measures 25 – 32. Showing synchronization point, electronic effect hairpin- and audio signs.

Figure 34. Kuuki no Sukima measures 25 – 32. Showing synchronization point, electronic effect hairpin- and audio signs.

Audio example #10: Harpa performance.

http://caveproduct.com/audio/H_Clar.m.25-32.wav

Audio example #11: Torshavn performance:

http://caveproduct.com/audio/T_Clar.m.25-32.wav

Audio example #11: Copenhagen performance:

http://caveproduct.com/audio/C2_Clar.m.25-32.wav

In measure 25 the Clarinet comes in with three repeated multiphonics (chords) that has a decreasing Delay and Granulation. At the same time, there is an increasing Reverb and Feedback effect. In measure 29 the Piano enters with a chord that goes into the fast-moving fragmentation of the same chord with increasing Delay and Feedback. In the Harpa example, the electronics are quite audible and close to expectations. In the Torshavn example, they have less volume, and the Copenhagen performance seems to be somewhere in between with the electronic level softer than in Harpa and louder than in Torshavn. An explanation can be slightly different placements of the microphones or the conductor choose a slightly different electronic volume level.

Different placements of the loudspeakers and the different acoustic between the halls can also be a factor.

Measure 18 – 32

Now looking back and listening to a video recording of the Copenhagen performance measure 18 – 32. As illustrated in the video the conductor raises the volume level during the long crescendo note in the Horn (measures 19-22) and then keeps that level until the Violin enters in measure 22. After that, she decides to lover the level a bit, afraid of getting a too strong signal and therefore increasing the risk of feedback. Soon after, the conductor feels secure enough to raise the electronic volume value up again.

Copenhagen performance of measures 18-32

Video example #9: http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph.m18-32.mp4

This video is an excellent sample of how the conductor can in real time adjust the balance between the sound level of the instruments and the electronics.

By looking at the same measures during the other performances then it becomes evident that the conductor is quite consistent increasing the electronic volume.

Torshavn performance of measures 18-32.

Video example #10: http://caveproduct.com/videos/Thavn_m-18-32.mp4

Unfortunately, at the Torshavn concert, the video camera does not catch the whole stage and is located on the wrong side of the conductor. It still gives an idea of the conducting progress. Here the conductor increases the electronic volume value a bit earlier than in the Copenhagen video but then does not adjust the volume the second time as before. Although I would have liked a bit more electronic volume, this example clearly shows that the conductor is in charge and makes her personal adjustments. Treating the electronic sounds precisely as she does when adjusting the volume level of the acoustic instrument. It proofs the success “the aim,” of the Bridging the Gap – ConDiS project to create a conducting tool that allows the conductor with “natural” conducting gestures to adjust the electronic volume value as well as adjusting the acoustic sound.

Video example #11: Harpa performance.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Harpa_m-18-32.mp4

As mentioned before, the Harpa concert had the most active electronic volume value of all the concerts. Probably due to the conductor not being able to hear the electronics as transparent as in the other performances. Still, she does very similar conduct during these measures as in the other performances. She increases the electronic value earlier than before and then makes a second adjustment by increasing the value a bit more one measure later. After that, she is satisfied with the balance and does not further adjustments in the following measures.

Measure 37 – 49

After the fermata in measure 36, the Score and the DAW get synchronized before the flute comes in. Here we can easily hear the electronic effects of delay and reverb as the flute continues to play (and sing). The electronic effects get even more audible as the strings, and the clarinet enters with an increasing delay, reverb, and granulation. This part is one of my favorites since it sounds very close to the sonority that I had in mind and ads a very elaborate sonic cloud to the chord progression.

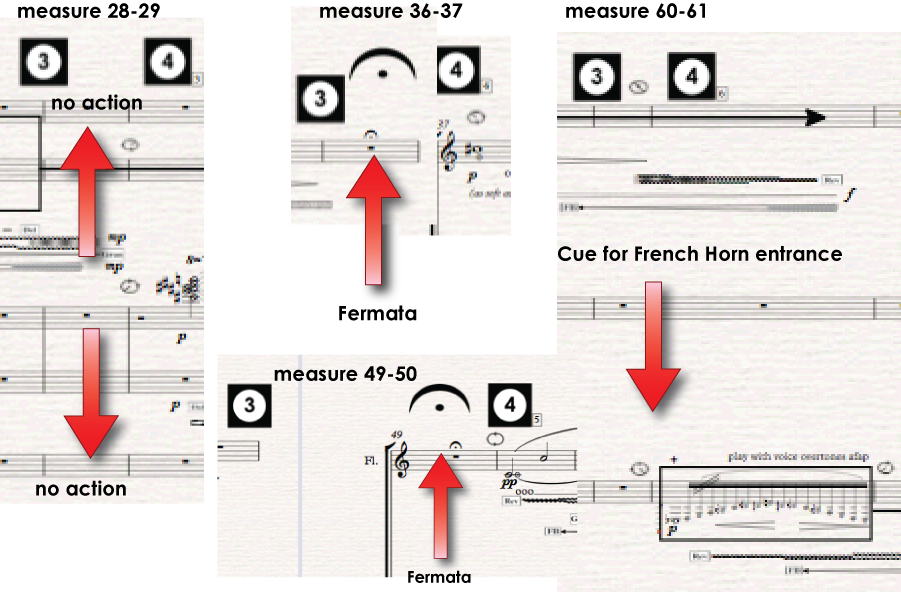

Figure 35. Kuuki no Sukima measures 37 – 49. Showing various electronic Fx hairpin in conjunction with DAW.

Figure 35. Kuuki no Sukima measures 37 – 49. Showing various electronic Fx hairpin in conjunction with DAW.

Figure 35 shows measures 37 – 49 and the connection of the Score to DAW. As can be seen, the volume of the electronic effects increases significantly after the multiphonics begin. The effect can clearly be heard by listening to the video recordings below.

Video example #12: Volume of Electronic Effects.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_M4.mp4

It is particularly interesting that the electronic sounds are very clear even though the volume of the instruments, which is the power source of the electronic sounds, is very weak. The main reason is that the effects are very open or strong f(about 85%). It, therefore, necessary to increase electronic volume if the acoustics are soft.

Synchronization cue

In the first movement, the compositional method focused on a simple, straightforward use of the synchronization knobs. i.e., the middle finger knob to start/stop, and ring finger knob (4) to jump and start. Therefore, in the beginning, the use of the knobs is made as comfortable as possible. It is, therefore, no coincidence that the first two synchronization cues happen before and after a fermata giving the conductor; time, breath and freedom.

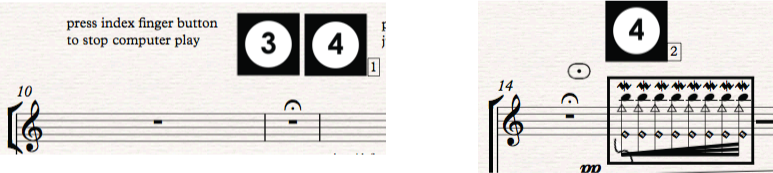

Figure 36. Kuuki no Sukima measures 10 – 15 indicating where to press knobs three and four to stop, synchronize and start.

Figure 36. Kuuki no Sukima measures 10 – 15 indicating where to press knobs three and four to stop, synchronize and start.

Next synchronization cue in measure 28 – 29 does not come on a fermata but comes in a measure where there is very little to conduct since there is only a clarinet ostinato[1]. Therefore, the conductor has a good time to press the knobs for stop and jump/start. The sync. cue in measure 36 – 37 and 49 – 50 occurs at a fermata as the first two cues.

Figure 37. Kuuki no Sukima. Showing various stop, synchronization and start playing cues.

Figure 37. Kuuki no Sukima. Showing various stop, synchronization and start playing cues.

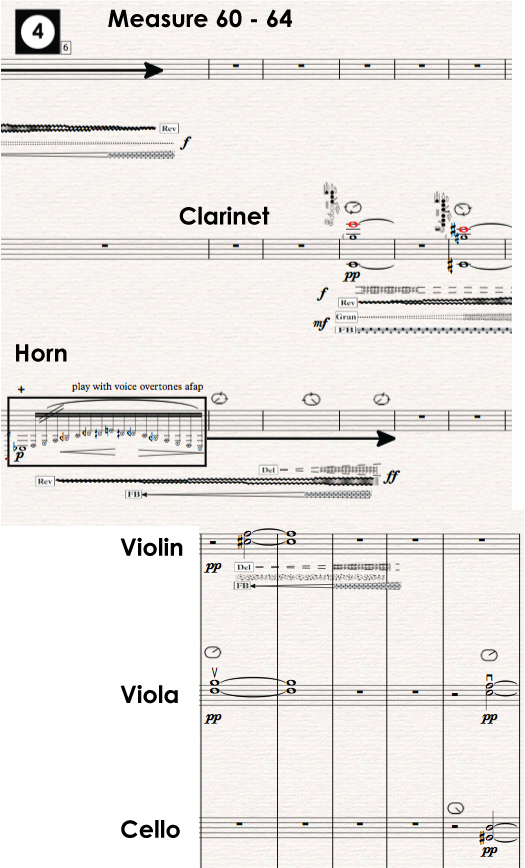

The following synchronization cue in measure 60-61 is slightly different from the others since here the conductor has to give the Horn player an entrance cue at the same time she synchronizes the Score and DAW. Still, all these synchronization cues are all at rather “pleasant” moments and continue to be so throughout the 1st. movement.

Harpa performance. Illustrated video example from the opening measures of Kuuki no Sukima.

Video example #13:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NwxfjLoe9Ek&t=74s

The Conductors Relationship to the Conducting Tool

In the score, there are few instances where an arm movement is written to indicate live variations in the instrumental and electronic mix. Although these indications are not necessary, since the conductor’s intuition for sonic balance should be sufficient, they are written there as an experiment to measure the conductors respond. The following focuses on the conductor’s use of her arm to control the overall volume of the electronics. How she follows the written arm movement indications as well as adding her own based on her musical sensitivity.

Use of Electronic Volume Control

1st. movement

Looking at performance as Schæffergården, the conductor activates the volume control seven times during the 107 measures of the first movement. The Schæffergården concert is chosen since it was the last concert of the four during the Nordic Tour. That means the conductor had got more acquainted and experienced with ConDiS and was using the glove’s possibilities in a more relaxed, freer and natural way than at the beginning.

Four of these seven volume controls are written in the score. Why? They are written in the score to learn how the conductor responds. It should be stated that I did not ask the conductor specifically to make changes there but told her that these could be interesting spots in the piece to adjust the balance of electronics and live instruments. The first volume control is at measure 3 and 4, see Example 1. It is well illustrated in the score with indications of how to activate and raise the volume level until deactivating at end of measure four.

Example 1

Activating volume control. Measure 3 and 4. (Schæffergården performance).

Video example #14:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl1.mp4

Example 2

Figure 38. Kuuki no Sukima measure 18 – 23.

Figure 38. Kuuki no Sukima measure 18 – 23.

The Bass Clarinet enters with a combination of crucial irregular slap and trill and soon after the Horn plays a note that has a crescendo from p(soft) to f (loud). At the same time, the conductor decides to give the Horn a bit more electronic support as can be heard in the below video clip.

Video example #15: Measure 18 – 23.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl2.mp4

The electronic effect is easily audible as the conductor raises her hand and therefore it is clear that she is affecting the overall value of the electronic sound. Since the conductor opens her hand in the uppermost position of the arm, the electronic value stays at a high value until she makes the next adjustment which occurs only a measure or two later (approx. measure 24) as can be seen in Example 3.

Example 3

Figure 39. Kuuki no Sukima measure 23 – 29.

Figure 39. Kuuki no Sukima measure 23 – 29.

Video example #16: Measure 23 – 29.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl3.mp4

It is clear that the conductor decides to lower the electronic sound value when she hears that the strings are getting a little bit strong. After the clarinet comes in the conductor decides to give it a bit more electronic sound value by raising her arm up to the almost top position. Then she decides to lower it a little bit and deactivates the volume control around 75% of the total value or with the arm just above the middle level. Keep in mind that the position of the arm and volume value can vary. It is all based on the relative position of the arm meaning that the calculation relates to the latest arm position value. This relative arm position calculation means that if the conductor deactivates volume control with 75% of its maximum volume value it would stay at 75% when activated again. No matter what position the arm would be. When the conductor activates the volume value control again, the arm is not going to be in the same position as the last time she deactivated the control. To have the computer remembering last arm position is done to avoid an audible jump in the volume level. Similar things happen in the next example from measure 63 – 68.

Example 4

Figure 40. Kuuki no Sukima measure 63 – 68.

Video example #17: Measure 63 – 68.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl4.mp4

In Example 4 the conductor decides to lower the electronic sound of the strings before the clarinet enters. After the clarinet has entered the conductor decides to play with the possibilities of the ConDiS by increasing and decreasing the electronic volume or in musical terms, make a crescendo and diminuendo at the beginning and end of each sustained multiphonic of the Clarinet.

These measures show a perfect example of a very positive and musical use of the ConDiS technology. Here the conductor is molding the sonority of the instruments and electronics using her musical talent to create a live “conversation” that would be impossible without live interactivity such as is available through ConDiS.

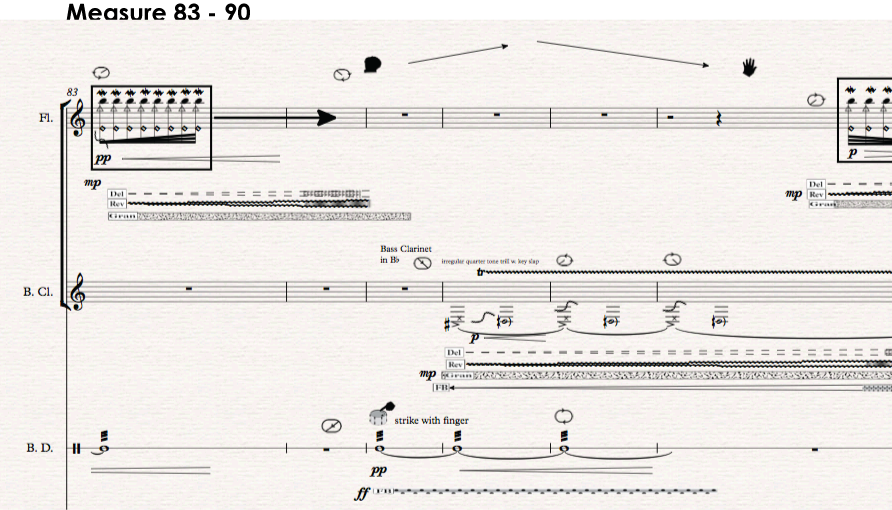

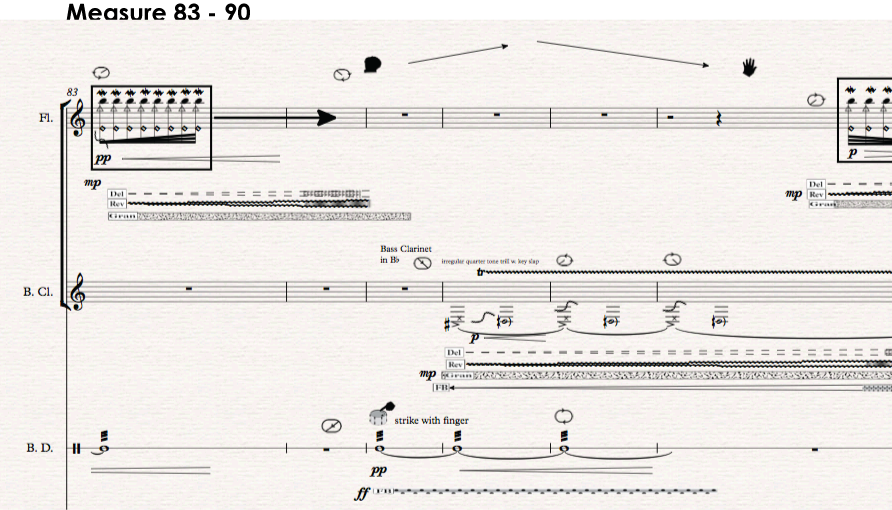

Example 5 from measures 83-90, shows instructions of volume value control in the Score.

Example 5

Figure 41. Kuuki no Sukima measure 83 -90.

Figure 41. Kuuki no Sukima measure 83 -90.

Video example #18: Measure 83 – 89.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl5.mp4

As can be seen from the video clip the conductor activates the volume control close to the given point and starts by decreasing the volume. Then when in full control she decides to give it a little bit of crescendo, then a bit more and finally before deactivation, she makes a diminuendo to her chosen volume level.

Since there is a written volume value change just a few measures after the last one, it is interesting to watch and hear how the conductor responds (Example 6).

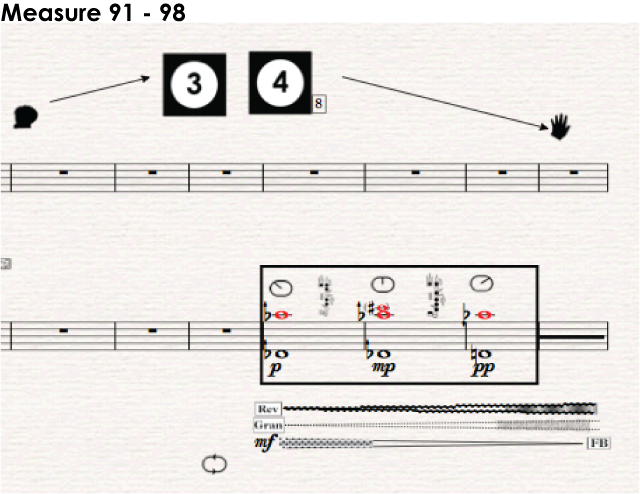

Example 6

Figure 42. Kuuki no Sukima measure 91 – 98.

Figure 42. Kuuki no Sukima measure 91 – 98.

Video example #19: Measure 91 – 98.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl6.mp4

At this spot, the conductor activates the electronics in a very high arm position. That means she has little headroom to increase the electronic volume value but plenty of room to decrease the volume. The outcome is that the electronic volume level goes down from the last level being approx. mf(mid-strong) to almost nothing or silence. Although the conductor then raises her arm a bit, it does not give much feedback since the music is already very soft. This arm position was not what was intended to happen. The intention was that the conductor would play more with the interaction as she did in the last example (example 5). Meaning that she would activate the volume control with her arm in a low position and raise the electronic volume to a maximum point before lowering it again. It raises the question, if the conductor is consciously or unconsciously on the brake, holding back, taking precautions against the risk of causing feedback. During rehearsals and also during the first performance in Dokkhuset we did have few incidences of feedback. It turned out that the conductor had a very sensitive ear for feedback and therefore a constant fear of having it happen again throughout the Nordic Tour.

Example 7

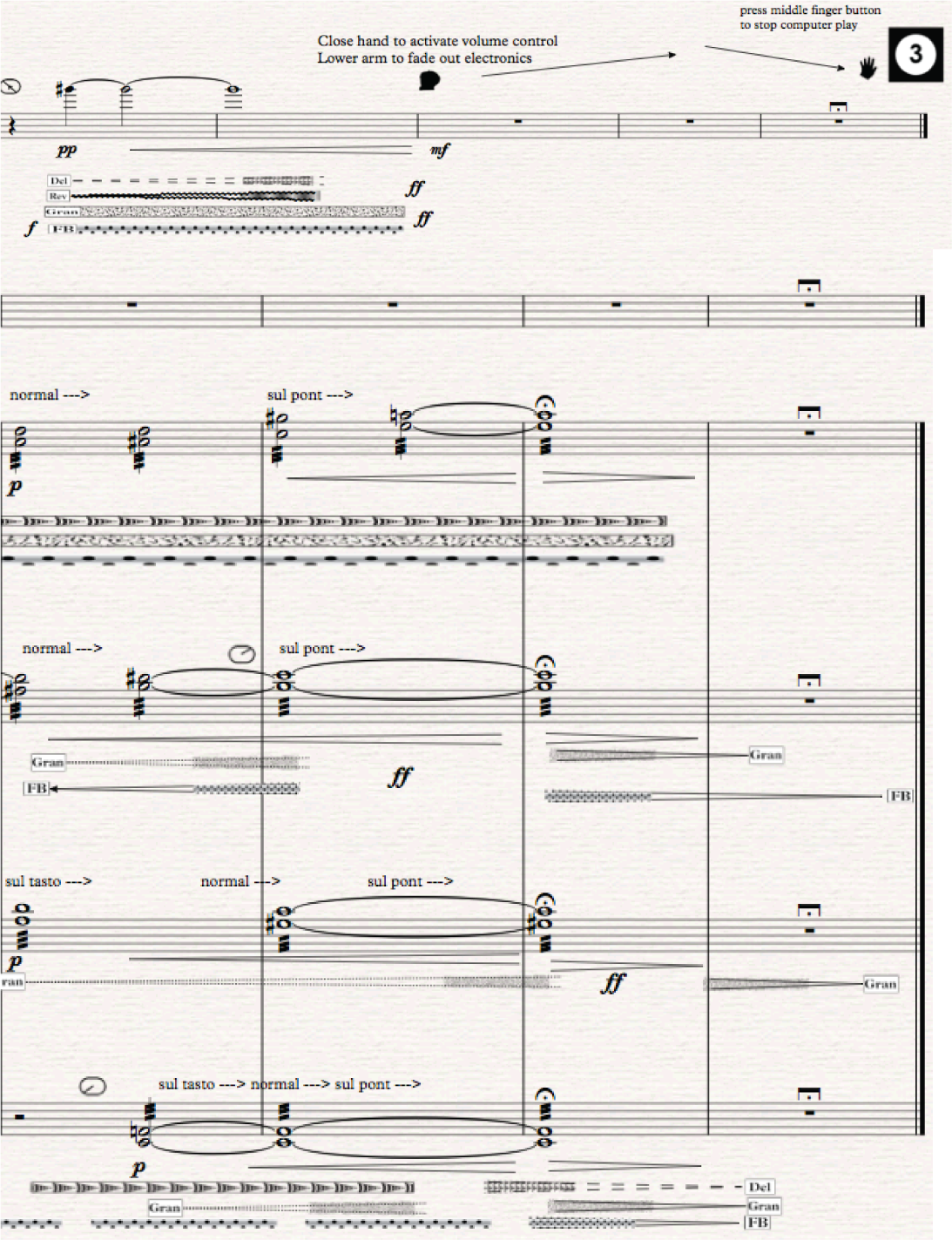

The last example shows the closing measures of the first movement. Here instructions are written to the conductor to activate the volume control and then lower arm to fade out the electronics at the end. The way, instructions are written (also in other examples with volume control) it can be understood that the composer does want the conductor to activate the volume control. Then to raise her arm and after that lower it for a fade out. Honestly, it is precisely the action aimed for; to show a clear relationship between the conductor’s gestures and audible electronics.

Figure 43. Kuuki no Sukima measure 103 – end.

Figure 43. Kuuki no Sukima measure 103 – end.

Video example #20: Measure 103 – end.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl7.mp4

As shown in the Video clip, the conductor follows the score exactly as written, but! The conductor activates the volume value control with her arm in the lowest possible position and then raises her arm up to approximately maximum level before lowering it for the final fade out. This gesture is precisely the conducting gesture wanted, but I was expecting more reaction from the electronics. That is, there would be more action, more drastic electronic volume changes. What went wrong? Why so little response from the electronics?

Figure 45. Conductor Halldis Rønning conducting at Schæffergården. Figure 45. Conductor Halldis Rønning conducting at Schæffergården. |

2nd. Movement

The second movement has more complexity and musical action. Therefore, less time for the conductor to adjust the ConDiS system. It is deliberately composed that way to find out where conducting information boundaries lies.

Example 1

After a fermata[2]and a sync. marker (knob 3 and 4) there is a left-hand pizzicato in the Double Bass a high note in the Violin and then a short Flute motive. This action shown with red arrows in Figure 53.

Although, I would have liked to have a bit more volume on the Double Bass electronics I must confess that the conductor does a quite interesting job. By not increase the volume until on the last sustained note of the flute the conductor gets a musical clarity between the instruments and the electronics.

This example is another excellent example of how the conductor can make instant musical decisions based on what she perceives.

Figure 46. Kuuki no Sukima 2nd movement. Measure 11 – 14

Figure 46. Kuuki no Sukima 2nd movement. Measure 11 – 14

Video example #21: Measure 11 – 14.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl8.mp4

Listen how the sustained note of the Flute gets an extra space when the conductor decides to add more volume value to that note. Keep in mind that this is not written in the score, here it is the musical judgment of the conductor. This kind of instant decision is very much in the spirit of the ConDiS and proofs the artistic value of the ConDiS system. It comes naturally, its ads natural feeling to the flow, it is spontaneous and therefore an extension of the interaction between the acoustic and the electronic sounds. This “communication” could never happen without the ConDiS system, giving the conductor the ability to shape the music through her musical experience and knowledge. It gives the conductor a musical tool to express her musicality not only the instrumental part but to the whole performance, instrumental and electronic.

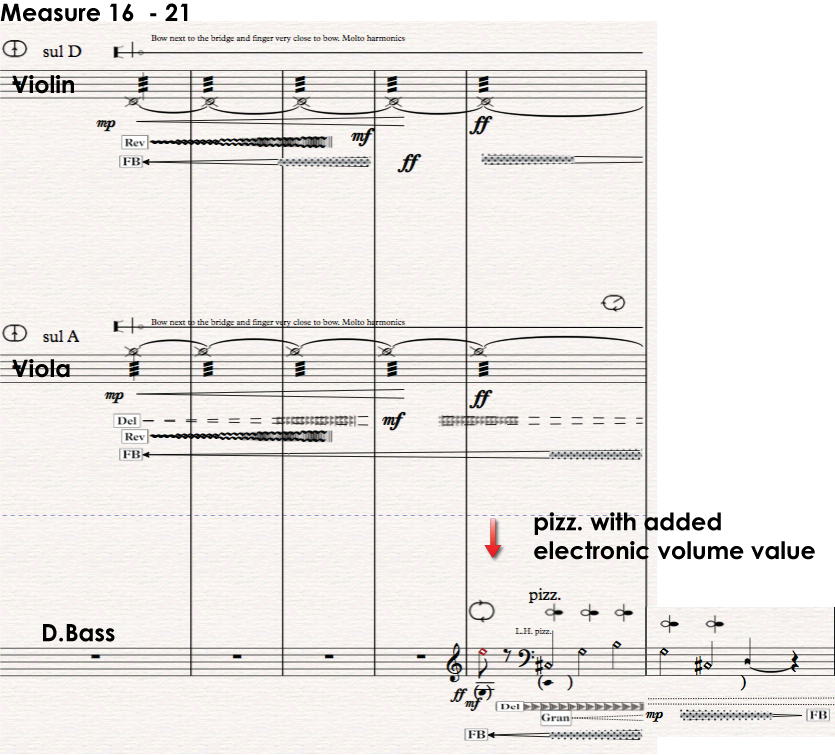

Example 2

The next example comes from measures 16 – 21 where the left-hand pizzicato motive from measure 11 is repeated. Again, nothing is written in the score for the conductor to adjust the electronic volume value. It is, therefore, her musical judgment to add more electronics to the pizzicato. By doing so, the conductor brings out slightly variated repetition causing an interesting effect, making the repetition much more effective.

Figure 47. Kuuki no Sukima 2nd movement. Measure 16 -21

Figure 47. Kuuki no Sukima 2nd movement. Measure 16 -21

Conductor ads electronic volume to the pizzicato motive of the Double Bass.

Video example #21: Measure 16 – 21.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl9.mp4

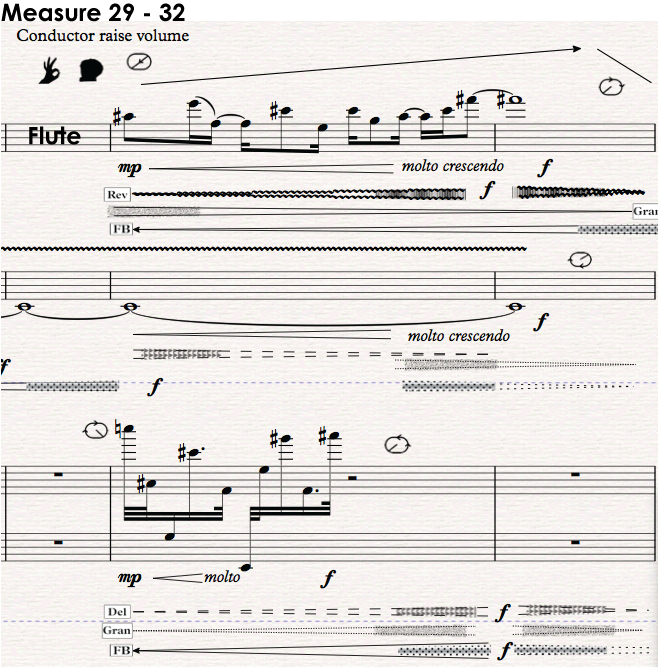

Example 3

Example 3 shows a written instruction to the conductor to activate and increase the electronic volume raising her arm. The OK sign written, is a leftover from earlier versions when the conductor could also activate panning and effect control with little finger and thumb up sign. Control that was unnecessary when pan and effect control were left out. The OK sign was left there as a security measure to double check that the volume value control is activated.

Figure 48. Kuuki no Sukima 2nd movement. Measure 29 – 32

Figure 48. Kuuki no Sukima 2nd movement. Measure 29 – 32

Video example #22: Measure 29 – 32.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl10.mp4

The conductor ignores the OK sign knowing that the function is no longer necessary. Therefore, it should be left out of the score.

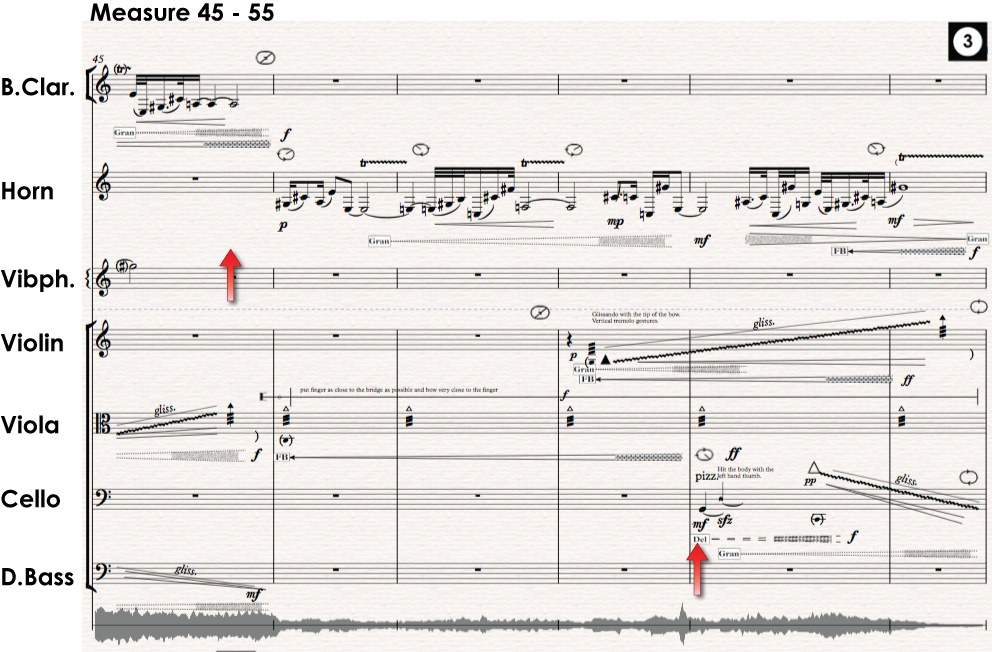

Example 4

The following shows another example where the conductor uses the ConDiS to make spontaneous volume control. In measure 46, when the Horn enters (red arrow) the conductor immediately brings down the volume value and keeps it low until measure 49. Then, as the cello enters with its pizzicato, a knock-on body, vertical bowing tremolo and glissando (red arrow), she increases the volume. By doing so, the conductor makes sure that the sonic effect of the cello is evident before adding the electronics.

Figure 49. Kuuki no Sukima 2nd movement. Measure 45 – 55.

Figure 49. Kuuki no Sukima 2nd movement. Measure 45 – 55.

Once again, the conductor uses musical intuition by keeping the Horn electronic levels all the way down to emphasize the electronics of the cello electronics with the pizzicato, knock and glissando sound.

Video example #23: Measure 45 – 55.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctl11-13.mp4

Example 5

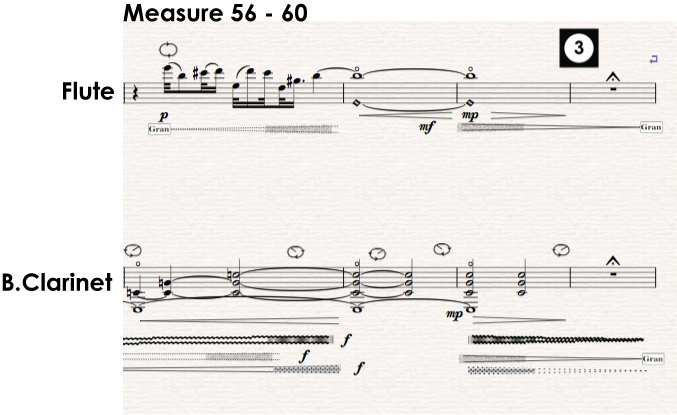

This example shows how the conductor controls the volume value in measures 56-60. At the beginning of this example, the electronic sound is rather loud. The conductor decides to lower it a bit and then plays with the volume control like she is phrasing the sound. The volume level moves up and down in conjunction with the music to make a perfect unity of the electronic and acoustic sounds. In the end, the conductor takes the electronic volume value all the way down before she stops the DAW (3rd knob) and jumps forward (4th knob). That way, the conductor uses her conducting skills and musicality to make a smooth transition from one phrase to the next.

Figure 50. Kuuki no Sukima 2nd movement. Measure 56 – 60.

Figure 50. Kuuki no Sukima 2nd movement. Measure 56 – 60.

This video example shows how the conductor is playing with the acoustic possibilities that open up using the ConDiS system. Watch how she turns the electronic volume down then a bit up and down before fading it out.

Video example #24: Measure 56 – 60.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl14.mp4

Example 6

This example comes from the closing measures of the 2nd. movement. Here there are written instructions for the conductor to activate the volume control and increase the electronic volume level before fading everything out at the end.

Figure 51. Kuuki no Sukima 2nd movement. Measure 83 – end.

Figure 51. Kuuki no Sukima 2nd movement. Measure 83 – end.

The conductor decides to activate the volume value control earlier than written in the score to have more time to play with the sound. This action is something we did discuss during the rehearsals and decided to leave the activation time up to the conductor and should be corrected. Earlier activation gives the conductor more time to play with the sound and should also be more effective since previous overall loudness is much higher than towards the very end. Unfortunately, the electronic sound level of the Horn is not very audible and indeed was like that during all of the performances. Although not critical for the ConDiS research, it should be looked at and fixed. Most likely a better microphone location will solve that problem. Still again another reason for underlining the importance of pre-concert preparation with a thorough sound check for each instrument as well as the whole ensemble.

Video example #25: Measure 83 – end of 2nd. movement.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl15.mp4

Looking at 3rd. movement of Kuuki no Sukima, the first instance of volume value controlling happens around measure 29. As can be seen in this example there are no written instructions. Therefore, it is entirely the conductor’s decision to control the electronic sound.

3rd. Movement

Example 1

Figure 52. Kuuki no Sukima 3rd movement. Measure 29 – 32.

Figure 52. Kuuki no Sukima 3rd movement. Measure 29 – 32.

As shown in the following video clip, the conductor adds electronics at the end of the piano phrase or where the Horn makes increasing air sound. The conductor is transforming the electronics and the acoustics the same way as she would be conducting one instrumental sound to another.

Video example #26: Measure 29 – 32.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl16.mp4

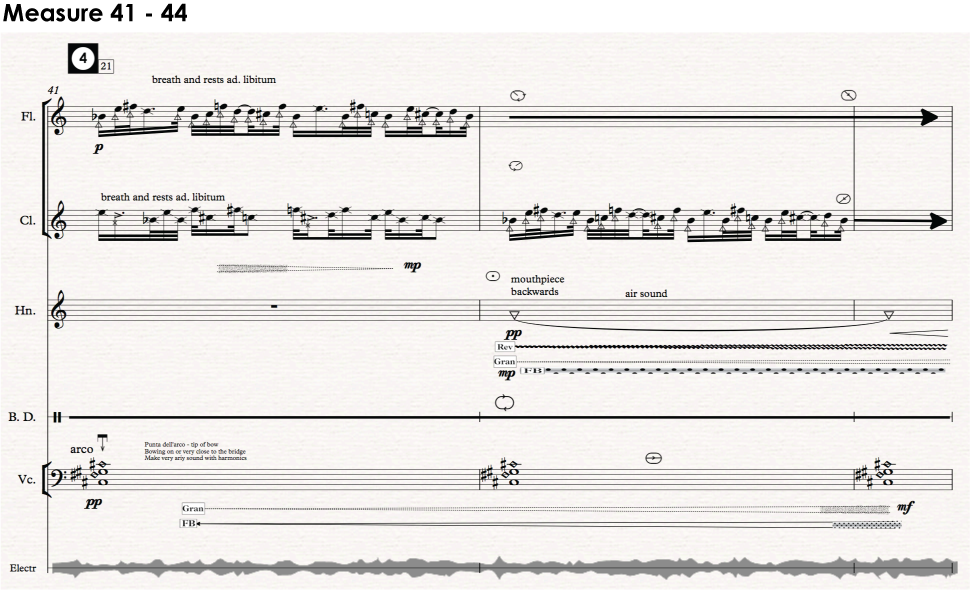

Example 2

The following example shows measure 41- 44. The attached video clip starts about a measure earlier and ends a measure later. The main reason being a page turn that was complicated to paste into such a small frame. In the missing measure before the conductor has to press the 3rd knob to stop the DAW and then in measure 41 press the 4th knob to have the DAW to jump (if it were off) and synchronize with the score at the beginning of that measure. At the same time, the conductor decides to activate the volume value control which is an interesting idea.

Figure 53. Kuuki no Sukima 3rd movement. Measure 41 – 44.

Figure 53. Kuuki no Sukima 3rd movement. Measure 41 – 44.

The video example shows how the conductor makes a slight mistake but corrects it on the fly. There she has to stop the DAW and jump to the next marker (knobs 3 and 4). She decides to close her hand for volume control but realizes that it was a bit too early, corrects it, does the knob 3 and 4 and then she activates the volume control. Important to notice the flow of the correction how “naturally” she opens her hand again, presses the knobs and then activates the volume control.

Video example #27: Measure 41 – 44.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl17.mp4

Example 3

The following example showing measures 54-63 is a good example of the use of the ConDiS system, as the conductor needs both to stop the DAW, synchronize and then set a new tempo (metronome 92). Immediately she decides to activate a volume value control to reduce electronic sounds, although not written in the score.

Figure 54. Kuuki no Sukima 3rd movement. Measure 54 – 63.

Figure 54. Kuuki no Sukima 3rd movement. Measure 54 – 63.

The accompanying video showing the same measures shows clearly how the conductor reduces the volume value of the electronics, probably because she has found the echo effects following the Pizzicato (plucked strings) to be too loud. Soon, she then decides to increase the volume so that the echo comes in. A perfect example of how the conductor herself determines the balance between the sound and electronics. The intention is to keep the echo effect strong at the beginning of this pizzicato section. The conductor’s interpretation is excellent and gives the music more life. There again it comes to the conductor’s role in the music performance. Even though accepted that the conductor’s job is to put themselves into the mind of the composer and interpret music from it, then it is inevitable that the conductor sets his mark on the performance. The fact that the conductor puts his character into the composition is for me, as a composer, very important. That way the music comes to life, from being black dots on the manuscript paper to a sea of sounds, tones, and chords.

Video example #28: Measure 54 – 63.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctl18-20.mp4

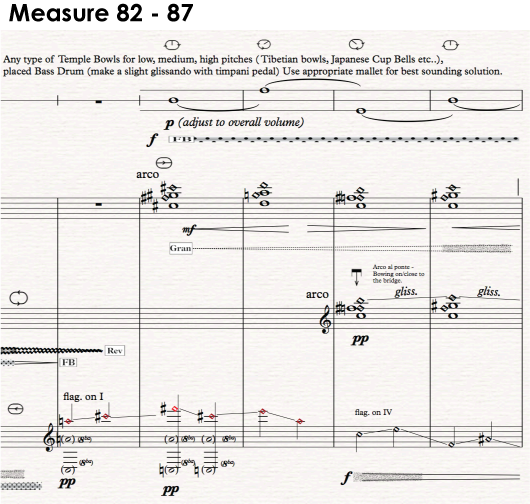

Example 4

The following example from measure 82-87 again shows how the conductor decides to activate the volume value control and add a bit more electronics to the performance. This section is very soft very subtle. Therefore, the electronic sounds are also very soft and subtle since they are all directly connected to the sounds of the instruments. Still, we can hear that there is a very subtle change of tone color as the conductor raises her arm. A movement in the piece that shows clearly how the ConDiS system can be used to make little nuances that are so important in music.

Figure 55. Kuuki no Sukima 3rd movement. Measure 82 – 87.

Figure 55. Kuuki no Sukima 3rd movement. Measure 82 – 87.

The following video shows the performance of the above score. Notice how the conductor decides to add more electronics to the mix and how it adds a slight color change to the harmonic spectrum.

Measure 82 – 87.

Video example #29: Measure 82 – 87.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl21.mp4

Example 5

The conductor makes a musical decision to take over the volume control and lower the electronics just before the piano enters. The conductor undoubtedly feels that the electronic level needs to decrease, sub sequentially making the piano entrance more apparent.

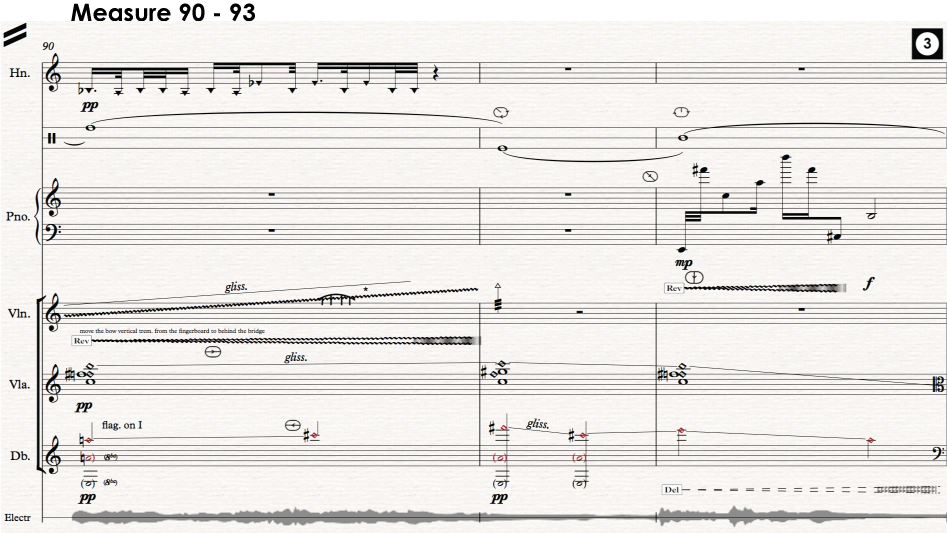

Figure 56. Kuuki no Sukima 3rd movement. Measure 90 – 93

Figure 56. Kuuki no Sukima 3rd movement. Measure 90 – 93

The conductor decreases the volume of the electronics right before the piano entrance.

Video example #30: Measure 90 – 93.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl22.mp4

Example 6

From measure 131 the conductor has instructions to activate the volume value control but seems to miss them. She also misses the written text in measure 134 which says “sempre volume control al fine” meaning the conductor can “improvise” the volume changes till the end of the piece. The use of “sempre” meaning “throughout” instead of drawing lines all the way to the end seems to be a little blurry. It is noticeable that the conductor does not activate the volume value controller until next time these lines are drawn in measure 142. At that point, she plays with the volume control for several measures but deactivates again in measure 147. Then, she waits until measure 154 (example below) where she activates the volume control till the end of the piece or measure 163. It is not unlikely that it might be uncomfortable for her to hold her hand closed for such a long time. She might also have needed to deactivate the volume to be able to make more expressive hand gestures. Another important fact is that there are hardly audible electronics towards the end. The conductor complained that it felt a bit uncomfortable not to hear or feel the electronic respond enough. Something that needs to be looked into and changed.

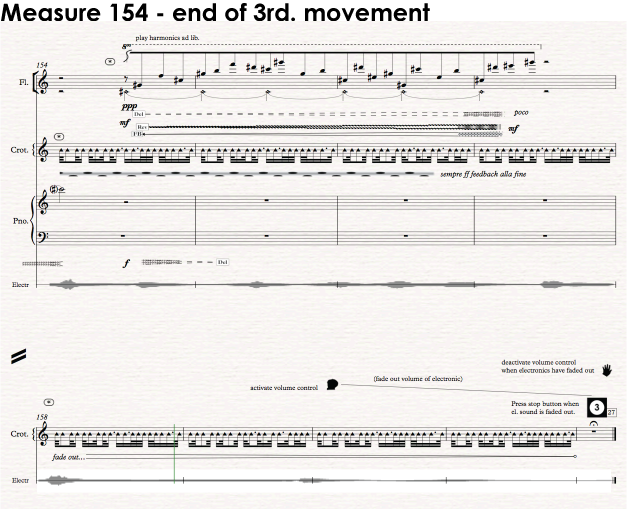

Figure 57. Kuuki no Sukima 3rd movement. Measure 154 – end.

Figure 57. Kuuki no Sukima 3rd movement. Measure 154 – end.

The conductor activates the volume control, brings the volume up and down until near the very end when she has it fading out. Then opens her hand to fade out the Crotales with both her hands. The overall volume of the electronics is a bit too soft and needs to be fixed before the next performance.

Video example #31: Measure 154 – end of 3rdmovement.

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl26.mp4

Comparison of Performances

Using examples from the first two movements of Kuuki no Sukimaa comparison is made of the conductor’s use of ConDiS. Harpa, Reykjavik and Schæffergården, Copenhagen concerts are chosen since they are the first and last performances of the Trondheim Sinfonietta Nordic Tour and should, therefore, give a good cross-section.

1stmovement

Example 1

Conducting instructions from measure three of the opening of the 1st. movement.

Figure 58. Kuuki no Sukima 1st movement. Measure 3 – 4.

Figure 58. Kuuki no Sukima 1st movement. Measure 3 – 4.

Examining the conducting gestures from the concerts at Harpa and Schæffergården[3], the following reveals.

Conducting at Harpa.

Video example #32:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/H_Vol.ctrl_.1.mp4

Conducting at Schæffergården.

Video example #33:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl1_.mp4

The opening measures of the 1st. movement shows that the conductor has an identical way to conduct. Not a surprise since the use of ConDiS accurately written in the score.

Example 2

Now compare:

Figure 59. Kuuki no Sukima 1st movement. Measure 18 – 23.

Figure 59. Kuuki no Sukima 1st movement. Measure 18 – 23.

Conducting at Harpa.

Video example #34:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/H_Vol.ctrl_.2.mp4

Conducting at Schæffergården.

Video example #35:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl2_.mp4

Although not written in the score the conductor in this example activates the volume value control at a very similar point. At the Harpa concert, the conductor activates the volume value control a bit earlier then decides to wait till after the Flute has ended. Then similarly to the Schæffergården she activates it again just before the Horn but deactivates it sooner in Harpa. Notice, that the Harpa concert was the first of four concerts and Schæffergården the last one. It is obvious that when conducting the last performance, the conductor has become much more comfortable and familiar with the use of the ConDiS conducting system.

Example 3

Again, the conductor follows instructions written in the score.

Figure 60. Kuuki no Sukima 1st movement. Measure 83 – 90.

Figure 60. Kuuki no Sukima 1st movement. Measure 83 – 90.

Conducting at Harpa.

Video example #36:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/H_Vol.ctrl_.3.mp4

Conducting at Schæffergården.

Video example #37:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl3_.mp4

The conductor follows perfectly the drawn in lines instructions.

Example 4

Finally, the closing measures of 1st. movement. The conductor follows written instructions identically.

Figure 61. Kuuki no Sukima 1st movement. Measure 104 – end.

Figure 61. Kuuki no Sukima 1st movement. Measure 104 – end.

Conducting at Harpa.

Video example #38:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/H_Vol.ctrl_.6.mp4

Conducting at Schæffergården.

Video example #39:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl7_.mp4

Example 5

There is only one other instance in the first movement, where the conductor activates the volume value control at the Harpa concert. It is around measure 60 soon after a stop and a synchronization jump.

Figure 62. Kuuki no Sukima 1st. movement. Measure 60 – 64.

Conducting at Harpa.

Video example #40:

The following shows the Schæffergården performance where the conductor activates the volume value control about 3 measures later.

Conducting at Schæffergården.

Video example #41:

There is a difference although not significant in how frequently the conductor activates the volume value control during these performances. At Harpa, the conductor activates volume control total five times while in the Schæffergården she activates it seven times during the 1st. movement. At Harpa, she misses the written instruction in measure 91-98 and makes no activation in measure 23-29 like in the Schæffergården performance. Before jumping to a conclusion let’s look at the other movements.

2nd. Movement.

In the second movement, written instructions for volume value control are written twice, once in measure 30 and the other at the very end of the movement starting in measure 85. Therefore, all other activations are the conductor’s decisions using her musicality or what she hears during the performance. Here we have a very different outcome since in the Harpa performance the conductor activates the volume value control only twice or exactly where there are written instructions while in the Schæffergården she activates it six times, in other words, there are four places where she decides to activate the volume value control. What causes these differences can have various explanations, but it seems that these causes may be as follows:

- The concert at Harpa was the first concert, and the conductor was, therefore, more careful.

- The fact that the battery of the conducting glove fell out of its box in the middle of 2nd. movement.

- The concert in Schæffergården was the fourth and the last concert of the tour. Therefore, the conductor got to know the work very well as well as the potential of ConDiS. She was therefore much more relaxed.

- At the concert in Harpa, the conductor had difficulty hearing the electronic sounds, speakers placed behind her, and therefore she had difficulties to hear and sense the reaction to her volume value control.

- That was the opposite of the final concert where she could hear very well the electronics and the reaction towards her control activation.

- The fact that this was a final concert might have encouraged the conductor to experiment and take even more advantage of the possibilities of ConDiS.

Figure 63. Kuuki no Sukima 2nd movement. Measure 29 – 32.

Figure 63. Kuuki no Sukima 2nd movement. Measure 29 – 32.

Conducting at Harpa.

Video example #42:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/H_Vol.ctrl_.8a.mp4

Conducting at Schæffergården.

Video example #43:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl10.mp4

The closing measures of the 2nd. movement.

Figure 64. Kuuki no Sukima 2nd movement. Measure 83 – end.

Figure 64. Kuuki no Sukima 2nd movement. Measure 83 – end.

Conducting at Harpa.

Video example #44:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/H_Vol.ctrl_.9a.mp4

Conducting at Schæffergården.

Video example #45:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/Cph_Vol.ctrl15.mp4

Interview with conductor Halldis Rønning

The following are reflections based on an interview with conductor Halldis Rønning soon after the Trondheim Sinfonietta, Nordic Tour.

Halldis conducted all the performances of “Kuuki no Sukima” at concerts in Harpa in Reykjavik, Iceland, Nordic House in Torshavn and Christians Church in Klaksvik, Faroe Islands and Schæffergården in Copenhagen, Denmark.

The conductor and the art of conducting is one of the main focus points in the Bridging the Gap – Bridging the Gap – ConDiS project. Therefore, the interview with Halldis is considered one of the critical points of the ConDiS artistic research and its reflections.

Video recordings are used as a narrative format since writing in words would not capture the content equally as well.

What is your opinion about the idea of expanding the conductor role by conducting electronic sounds?

Video example #46:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/1.idea-of-ConDis.mp4

Is there an Artistic need?

Video example #47:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/2.artistic-need.mp4

Controlling Video?

Video example #48:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/3.adding-video.mp4

The threshold of Complexity?

Video example #49:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/4.too-much-info.mp4

What does the conductor do differently with the music when able to conduct the electronic sound as well as conducting the traditional way? Is there a feeling of fusion of the roles of the conductor and performer?

Video example #50:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/5.What-C-do-dif.mp4

How does the conductor feel using the ConDiS, does it feel natural toward her way of conducting?

Video example #51:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/6b.feel-of-tact.mp4

The importance of being able to have more than one concert to get more acquainted with the music, the conducting glove, and the stage setup.

Video example #52:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/6.How-C-feel-ConD….mp4

Did a different location of the loudspeakers make a difference?

During the “Nordic Tour” performance took place in different “concert” halls with different placements of the ensemble.

- Did a different location of the loudspeakers make a difference?

- Did a different resonating hall make a difference in the performance?

- Did a different location of the ensemble make difference for you?

- Ensemble located on stage behind the front speakers. (Harpa)

- Ensemble located on stage with front speakers on their sides. (Nordic House and Christians Church, Klaksvik)

- Ensemble located on stage with front speakers behind. (Copenhagen)

Video example #53:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/7.0.Loc-of-spker.mp4

Video example #54:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/7.II.res-diff-loc….mp4

Did a different resonating hall make a difference in the performance? Probably the piece benefits from some space.

Video example #55:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/7.I.res-diff-hall….mp4

How can I improve the Conducting Glove “ConGlove”?Page turning!

Video example #56:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/9.Pturn-and-Glove….mp4

What musical parameters should the conductor be conducting? Volume, tempo, spatial sound location etc.…

Adjusting the parameters?

Video example #57:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/9.II.adj-param.mp4

About adding new parameters: Panning control?

Video example #58:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/9.III.pan-ctrl.mp4

Leave it for the next piece: A concert for Conductor, Video, and Orchestra.

Video example #59:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/9.IV.next-piece.mp4

How about the idea of adding a baton (stick)?

Video example #60:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/9.V.Add-baton-2.mp4

Changing knobs functions?

Video example #61:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/9.VI.bton-funct.mp4

The written musical Score?

The complexity of the Score and writing of electronic sound information?

Video example #62:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/10.I.cplex-score.mp4

The use of colors in the Score?

Video example #63:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/10.II.col-in-scor….mp4

The size of the Score – the reduced Score?

Video example #64:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/10.III.Score-redu….mp4

Is there a need for visual aid such as iPad screen etc.?

Video example #65:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/10.IV.screen-aid.mp4

The anxiety of receiving an overload of feedback.

The danger of Feedback.

Video example #66:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/11.fbck_dngr.mp4

The danger of Feedback part 2

Video example #67:

http://caveproduct.com/videos/11.II.fbck_dngr2.mp4

Reflections on Interview with Halldis Rønning

The fragility of the ConDiS system during performance

As clearly stated in the interview with conductor Halldis Rønning there were some difficulties using the ConDiS during the performances. The primary problem was that especially during the first concerts she did not get as much sonic response when using the conducting glove. She had difficulties to know how much volume to add and even difficulties to know how much the electronic volume would respond to her gesture. During rehearsals and the first performance at the Dokkhuset in November, a feedback problem occurred causing her to become nervous and cautious using the volume function of the ConDiS system. This fear of getting a feedback loop into the system seems to have infected the performers since, according to their answers[4], had some trouble concentrating on their own performance knowing that things could go wrong.

Although the ConDiS conducting system was for me a successful research I am aware that there were few things that could go better. Mixed music performance of this kind, where there is a live real-time sound processing is in its nature always fragile. Feedback is a problem that increases proportionally with larger group of performers. On the other hand, the fact that the feedback “problem” seemed to disappear as the conductor got more used to the function of the ConDiS is a good sign. Although not able to conclude, it seems to me that the conductor with experience was able to keep the feedback under control.

Volume level “headroom”

The problem of steering the overall volume of the electronic sounds is a complicated task and is still a problem. The reason being that if the instruments are playing a soft passage the conductor has a very little volume to control. This is based on the fact that all the electronic sound source is directly related to the performing instruments. If the instruments play softly a very low sound level feeds into the audio system hence very soft electronic respond. If the conductor, then tries to raise the volume level of a very soft sound source there is a very subtle change which can lead to a feedback. If on the other hand, the volume level of the instruments is very loud the conductor has much more „headroom,“ meaning the conductor can change the volume level of the electronics much more drastic. To put this into more musical perspective the problem can be explained by following metaphor: If the instruments are playing very softly or ppp the audio level of the electronics can vary from silence (volume 0 or 0%) to max p(30%). If the instruments are playing very loud fff the audio level of the electronics can vary from silence (0%) to fff (100%). This respond difference was a bit problematic for the conductor and made it more difficult to get the “feel” for the volume control function.

From an artistic point of view, this practical and partly technical problem did affect the overall artistic outcome of the performances. The sonic outcome was different from one performance to another. During the Nordic Tour, the first concert in Harpa had the most electronic volume value with lesser electronic volume during the other performances. One explanation might be that at the Harpa concert neither the conductor or the performers could hear the electronics or as Cellist, MarianneBaudouin Lie wrote in her answer to the question if a different location of the ensemble made a difference:

Ensemble located on stage behind the front speakers. (Harpa)

Here I could hardly hear the electronics and it felt a bit like not being part of the work, like just being “the ensemble” and not inside the music. I was also uncertain as to whether the audience were hearing enough electronics.

It is possible that this lack of hearing the electronics caused the ensemble to play louder or the conductor to use more volume control than during the other concerts when they did hear more the electronics. I was placed behind curtains to the side of the stage and could neither hear clearly the electronics nor the ensemble. According to my memory, the conductor’s use of volume value was not unusually different from the other concerts. Therefore, am I leaning towards the explanation that the sound engineer located at the back of the hall did his to increase the overall electronic volume value.

When composing “Kuuki no Sukima” I was fully aware that writing a very soft sounding piece would cause more problems than writing a composition with a higher sonic level (loud). But that was part of the research, I really wanted to create a composition where all the sounds were soft, and one would have to listen carefully to each sound to hear the slightest detailed changes. Perhaps a failure of my behalf not to write a composition that included more volume changes or at least one moment with more loudness to demonstrate and the usage of ConDiS. Perhaps I should have written a composition giving the conductor more time to explore and play with the volume control. Why not have a section where the strings play long sustained notes and the conductor can play with the volume or mix between the instrumental and electronic sounds? Why not write a composition where…? These questions can only be answered with new compositions.

Reflections from the Performers

Shortly after the Nordic Tour, a questionnaire was sent to the members of the Sinfonietta. The following are my reflections to answers submitted by three members of Trondheim Sinfonietta.

- What is your opinion about the idea of expanding the conductor role by conducting the electronic sounds rather than a sound engineer? Is there an Artistic gain?

It is their common conclusion that the idea of expanding the conductor’s role is a positive development. Marianne feels as it is more part of the performance, giving an extra tension to the electronics whether or not everything works.

Peter mentions the possibilities that the conductor (any conductor) wearing the glove “would become more creative with it” while Trine points out the fact that it makes the performance unique from time to time.

Their answers are all rather positive and reinforce the view that ConDiS is a step in the right direction. The fact that musicians experience each performance differently, that they feel the electronics as more part of the whole, and that they give more attention to the electronics is very positive. This completely corresponds to the ConDiS conceptual ideology to expand the possibilities of live concert performances. To open up the gate of new possibilities to create creativity that only can be done by the performing artist on stage.

- With the conductor being able of controlling the electronic sound as well as the acoustic. Does that change your perception of the conductor’s role?

Marianne mentions that it makes her “pay more attention to the things she does with the glove.” Peter mentions that the role of the actual “Conducting” needed to be more complicated especially when it comes to metric changes “it might change rather more.”

Trine, on the other hand, mentions that it gets the conductor more to keep track of with the extended possibilities to “make mistakes etc.” that might not be a positive additional role.

Judging from their answers, in general, it does not. The extended role of the conductor enabling control of the electronic sound does not change their perception of the conductor´s role. This finding is very positive and shows that the goal of the Bridging the Gap – ConDiS project to develop a system that is a direct continuation of the conductors classical conducting gestures has in some way succeeded. That is also important from an artistic point of view since music performance is about the music, not about the extended role of a conductor neither technical solutions of technological problems.

It is true what Peter mentions when talking about the complexity of the actual “Conducting” meaning the traditional conducting without the extension of ConDiS. This was a compromise I made at the beginning, to write the whole piece in 4/4 with no metric changes. I was afraid that if I would go into that category the complexity of the whole project would be too much. Too much and therefore as Trine mention make extended possibilities for mistakes. Although mistakes are an important part, positive or negative, of live musical performance I was afraid that if the work would be too complicated, the music would be more about technical experiments than artistic (musical). I do agree with Marianne when she writes “I’m impressed that she has learned to use it as well as concentrating on everything else in the score.

I felt as I needed to give the conductor a break. Perhaps I was wrong, perhaps I should have added metric changes into the composition. These questions will never be answered except by writing a new piece of music.

- How does it feel watching the conductor using the ConDiS? Is it “natural”, confusing or distracting when she moves the conducting glove?

Answers to this question were quite emphatic in the sense that they all found it quite disturbing to see the conductor use the ConDiS conducting glove. Trine is very straightforward when she writes “Most disturbing” although not in the sense of visual disturbance more from a comment made by the conductor complaining about problems controlling volume and electronics. Marianne is in line with Trine mentioning her worries “wondering if anything is going to go wrong.” Then Marianne mentions the accident of the battery falling off as happened at the Harpa performance. Peter mentions the possibility of “mistaking an expressive gesture in the left hand for something to do with the electronics and vice versa”

It was a surprising fact that what distracts the performers watching the conductor using the ConDiS conducting glove, is more their fear of technical problems rather than watching her wearing the glove. I had imagined the design or the object, the glove, being a visual distraction but giving the answer it is not. The fear of mistakes or failure is not new to performer’s and it is interesting to see that crystalize in a fear of technical mistakes.

Only Peter mentions the possibility of confusion between conducting electronics and instruments in the expressive gestures in the left hand. This is a very valuable point, something that got me worried in the development process. When making the decision of extending the conductors job using gestures as close to his traditional conducting gestures I was fully aware that the “electronic” expressive conducting could be confused with the instrumental. Therefore, to a certain extent, I am pleased when Peter adds: in “Kuuki” it wasn´t really a problem, but I can imagine it might be in a different piece.” What Peter is saying is that in my composition I consciously kept the conducting demand from the danger of confusion between the electronic and instrumental-expressive conducting gestures. Perhaps I did so but then totally unconsciously, more likely the conductor Halldis Rønning did solve that problem with her conducting experience.

With the exception of fear of technical problems and the battery falling off at the Harpa performance, the use of ConDiS was very little distracting or confusing for the performers. I had the feeling that as the tour went on they paid less and less attention to the fact that she was wearing a digital glove and that “the object” became less part of the performance.

- Should additional information about the electronics be written in your musical part such as reverb and delay? Is less more? Anything else?

Both Marianne and Peter are aware that too much information can be dangerous. Marianne thinks it is not that important since she is “not in charge of steering anything.” Peter has a similar opinion based on the fact that he did not “hear anything.” Trine, on the other hand, has a slightly different opinion stating that it would be nice to know what kind of effect is intended. More importantly, she adds her view of the performer to be able to “optimize the effects.”

The equilibrium of information written into an instrumental score is an eternal problem. When is enough, enough? In the original instrumental parts given to the performers, all information, meaning all electronic signs were left in the parts since it was my opinion, like Trine mentions; it helps the performer to “optimize the effects”. I happened to be wrong, most of the performers got confused and asked these signs to be left out in future versions.

Writing electronic signs into the instrumental score happened to be a wrong decision, mainly since the action and reaction were too far apart. I am convinced that if the performers could have heard more easily the respond of the electronics linked to their playing they might have had an easier way to link electronic signs to the instrumental score. The fact that Marianne mentions that they are not needed since she is not in “charge of anything” and Peter agrees since he does not “hear anything” supports my opinion.

Therefore, a good solution has to be found in the form of a better placement of microphones and a better an onstage monitoring. As mentioned before there was very little time for sound test and no on-stage monitors were used to avoid feedback.

- During the “Nordic Tour” performance took place in different “concert” halls with different placements of the ensemble.

- Did a different resonating hall make a difference of the performance?

Marianne and Trine agree that a different resonating hall does make a difference while Peter becomes less and less aware of the electronics. He is right when he mentions that we (me and the conductor) were more careful in the smaller halls. It was my experience that more resonating halls did create as Marianne writes; “more unity of the acoustic and the electronic sounds.”

- Did a different location of the ensemble make difference for you? Can you describe the difference?

- Ensemble located on stage behind the front speakers. (Harpa)

They all agree that the placement of the loudspeakers in front of the ensemble in Harpa made it very difficult for them to hear the electronics. They all felt as they were playing without any electronic respond Marianne going as far as saying “I was also uncertain as to whether the audience was hearing enough electronics.”

It is understandable that placing the loudspeakers in front of the ensemble or perhaps better to say place the ensemble behind the loudspeakers makes it difficult for them to hear what comes out. Still, that they did hardly hear anything was a bit surprising, believing that they would hear some the acoustic from the hall.

The fact that the Harpa concert had the loudest electronic sounds strengthened further my view. The fact that the performers did not hear the electronics created the circumstances that they did play bit stronger or louder. For the same reason, the conductor added more electronics to the performance. Hence more electronic sound than at any other performance.

It was very difficult for me to hear the performance since I was located behind a curtain (hidden from the audience) to the side of the stage. Afterward when listening to the performance of Harpa I am quite pleased with the acoustic or the overall mix. The electronic sound level is a little too strong, but I like that range of clear instrumental sound to where you are not sure if you hear the instrument.

- Ensemble located on stage with front speakers on their sides. (Nordic House and Christians Church, Klaksvik)

Trine answer this question as the solution the felt best since she could hear the electronics as well as the others in the ensemble. For Marianne “it worked better” but she is still not happy with the levels of the electronics “I just couldn’t hear the electronic part.” She ends by quoting composer Sunleif Rasmussen who thought the acoustic in the hall and the electronics created a good unity, especially at the Christians Church.

At the concert in the Nordic House and the Christians Church the acoustic was a more wet meaning there was more resonance, especially in the Church. The front loudspeakers were placed to the back of the ensemble and the back speakers behind the audience. At the Nordic House, the front speakers were about 3 meters above the stage back speakers were about 5 meters above the stage since the audience platforms stood up from the stage. At the Church, the audience platform was on even level and all the speakers about 3 meters above the stage/audience.

At these concerts, it was easier for me to hear the overall mix of the performance as I was located to the back of the audience with the back speakers at my side. I agree with Sunleif that the “unity” between the instruments and the electronics was very good at the church performance perhaps the best during the whole tour. I would have liked the electronics to be just a bit stronger at both concerts especially at the Nordic House. It occurred to me that the more the conductor heard of the electronic sounds the less volume she added to the performance. Not such a surprising discovery, considering our different background.

- Ensemble located on stage with front speakers behind. (Copenhagen)

Marianne’s answer says it all: Here we felt like a part of the entire work, and I think this affects the way we play and the way we imagine the music. So, I think this is the best location of the speakers – keeping both the ensemble and the audience inside the circle of sound. I think it is then also easier to give more as a performer.

The placement of the loudspeakers at the Schæffergården in Copenhagen was similar to the performances in the Faroe Islands except the front speakers were more to the side. The hall was drier, meaning less resonance and according to conductor Halldis Rønning the concert where she could hear and feel the best response of the electronics sounds towards her conducting.

- Can you describe your personal experience during the concert performance?

Their answers to this question are very similar. Marianne and Peter mention a couple of difficulties in hearing their playing and the sound changes that follow. They all agree that it was fascinating when they heard them, but at the same time as Trine reads: A little odd to give away the “control” about a sound or effect since it is then processed and “distorted.”

Following are their written answers, as they are very descriptive of the performer’s experience.

Marianne

I had difficulty trusting the sound I was hearing, which is difficult being an acoustic musician used to orientate everything from what I hear around me. This felt better when the ensemble was within the circle of sound. I could also not let go of worrying about something not working, but maybe it is always like that with acousmatic/ mixed music? I enjoyed playing when I could hear the effect the music was creating, feeling like a small part in a big mix.

Peter

As I mentioned I was difficult to get the whole picture from where I was sat. For myself, I was pre-occupied with what I had to do personally and was pleasantly surprised (but I hope not distracted…) when I became aware for the electronics, especially when they were generated by something I had played.

Trine

Spennende klanger. Litt rart å gi fra seg “kontrollen” over en klang eller en effekt, siden den blir bearbeidet og «fordreid».

Exciting sounds. A little odd to give away the “control” over a sound or effect since it then is being processed and “distorted”.

Different background

Here I would like to use the opportunity to touch a critical point.

During the whole period from the first rehearsal to the last performance, a slight artistic difference between me as a composer of mixed music and Halldis Rønning conductor of acoustic music became more and more apparent.

The basis of the idea of having the conductor conducting the electronics is what I believed to be the best “musical” solution. The conductor must be the best-qualified person for the job as I have stated and explained many times during my writing.

Unfortunately, I must confess one oversight, and it is the fact that, for the conductor of acoustic music, the electronic sounds are exotic and, in some ways, disturbing.

Halldis experience of mixing instrumental sound and electronic sound is considerably different from my own experience. I have worked with electronic sounds for decades, and they are a part of my sound world. Halldis, on the other hand, has worked mostly in the world of acoustic instrumental sound and therefore these sounds are part of her sound world. It was therefore fascinating, but at the same time challenging to realize the developments that took place during the Nordic Tour from the first Harpa concert to the last concert at Schæffergården. Development that was in the sense that conductor Halldis Rønning lowered the overall electronic sound level as she due to better speaker location heard them more clearly. That reaction can only be explained to the fact that she is so familiar with the “classical” instrumental sound that she unconsciously kept the electronic volumes down.

This discovery was unexpected, but not surprising. It is my opinion that ConDiS is very exotic tool/instrument for the conductor. It is not only an extension of the conducting job it is an extension of the concoctor’s sonic world. With the electronics so closely related and responding to the conductors gestures the conductor becomes more aware of the electronic sounds. The conductor starts to hear the electronic sounds different than before when they were just an accompaniment to the instrumental performance. The conductor starts to hear the mix of the instrumental sounds and the electronic sounds in a different way. What is more, the performers share a similar experience. Therefore, the conductor, the performers, and the electronics become one; they become unity.

It is evident that it will take a long time to get ConDiS integrated into the performance of mixed music. It will take time not only, as I thought at the beginning of my research, because it is a new exotic tool for the conductors, but also because it extends their sonic world. They need time, they need practice, they need more performing opportunities. That can only happen with new compositions using the results of the Bridging the Gap – ConDiS project.

Reaction from the Audience

The following is a summary based on conversations I had with the audience right after each performance of Kuuki no Sukima. During these conversations, the following questions were the main topics.

- What is your opinion about the idea of expanding the conductor role by conducting the electronic sounds?

- Is there an Artistic gain?

- Can you describe your personal experience during the concert performance?

The most common answer to the expanded conductor’s role was: What did the conductor do with the glove?

These reactions were exactly the reactions that I was hoping for since they proved to me that I had succeeded one of my primary goals. Throughout the entire development and research process, my main goal was to expand the conductor’s ability to control the electronics, as “natural” as possible, without any extra-musical gestures or other show-off gimmicks. It also contains an indirect answer that could be interpreted as a positive reaction.

About the question of artistic gain, the audience’s response was in general that they needed better insight and knowledge of the subject to answer the question clearly. However, they agreed that they had experienced an exciting sonic world that was very exotic to them. They had experienced performance that definitely contained artistic gain.